If I asked you to define “repent” or “repentance,” what would you say?

We know it’s the thing you’re supposed to do when you’ve sinned and you’re coming to God asking for forgiveness. But is it just saying you’re sorry?

In English, “repent” means to express regret and remorse. While the Hebrew and Greek words translated “repent” in the Bible include that aspect of regret, the Biblical concept goes a step farther. Biblical repentance involves change. This change is a movement; an alteration in the direction of your heart and your life. The word image contained in both Hebrew and Greek is to turn away from sin and to turn toward God.

Unpopular Repentance

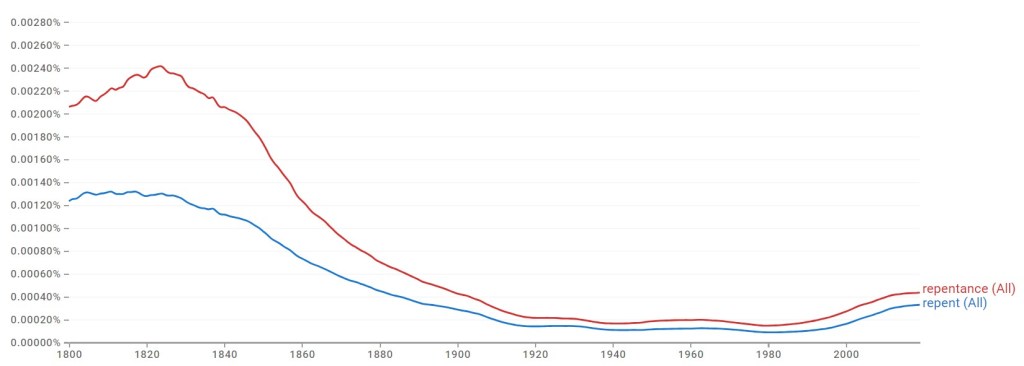

According to Oxford Languages (via Google), “repent” means “feel or express sincere regret or remorse about one’s wrongdoing or sin.” It came into Middle English “from Old French repentir, from re- (expressing intensive force) + pentir (based on Latin paenitere ‘cause to repent’).” There’s also something interesting going on with Google’s tracking for how often this word was used in English-language books between 1800 and 2019.

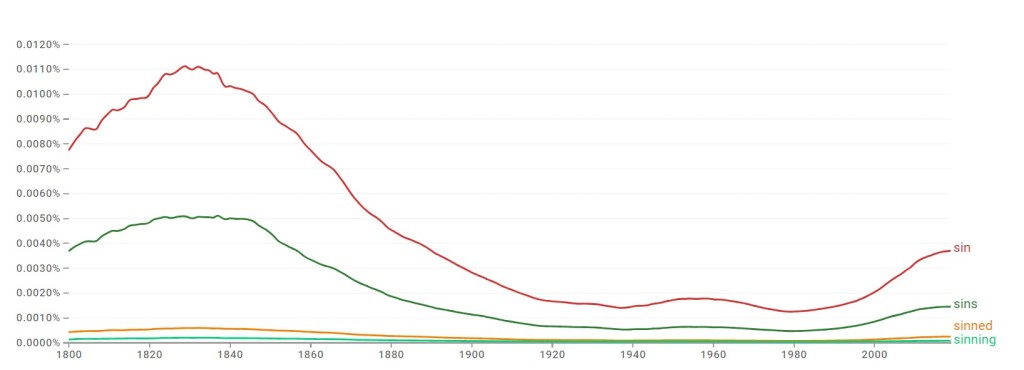

Evidently, repentance is not a popular idea (though I am intrigued by the recent uptick in usage after that slump in the 1900s). I don’t really think it will surprise any of us that “repent” and “repentance” are used less now than they were in the early 1800s. Repentance is something you need to do after you sin, and sin isn’t something we like to think about either. The more moral relativism takes hold in our society, the less people are willing to acknowledge sin is even a real thing since sin is the transgression of (God’s) absolute laws. The chart for “sin” in English language books looks very similar to the one for repentance.

But what about us today? If we’re sincerely following Jesus and love Him, He says we’ll obey His commandments. Commandments are contained in the law of God (Matt. 22:36, 40). The law and commandments are “holy, righteous, and good” (Rom. 7:12), and it is how God lets people know what sin is (Rom. 7:7-8). John says, “Sin is lawlessness” (1 John 3:4, WEB) or “the transgression of the law” (KJV). Paul further adds that “all have sinned” (Rom. 3:23). When Jesus came to this earth, one of His stated purposes was to call “sinners to repentance” (Luke 5:32), and it’s a message His disciples continued to preach (Acts 2:38; 3:19).

Putting all that together, we see that every human being is guilty of sin. Jesus can fix that problem, though. When sinners repent and follow Him, He takes away their sins (John 1:29; 1 John 3:5). Even after that, though, we still have a responsibility to keep His commandments because we love Him. And if we sin, then we need to repent again.

Returning and Changing

In Greek, one word translated “repent” is metanoeo (G3340). It includes the “regret or sorrow” aspect that is captured by the English word “repent,” but it also involves another step. The root words are meta (G3326: to be among or amidst, or to move toward that position) and noeo (G3539: “to exercise the mind, think, comprehend”) (Zodhiates entry G3340). Metanoeo is distinct from regret (metamelomai [G3338]) and includes “a true change of heart toward God” (Zodhiates). Thayer defines metanoeo as “to change one’s mind for better, heartily to amend with abhorrence of one’s past sins” (Thayer entry G3340). There’s a sense of turning around involved, as if when we sin we are walking away from God and when we repent we turn around and go toward Him again.

There’s another word for repentance in the New Testament as well. Zodhiates writes, “Metanoeo presents repentance in its negative aspect as a change of mind or turning from sin while epistrepho presents it in its positive aspect as turning to God” (Zodhiates entry G3340). He also notes that both of these words “derive their moral content … from Jewish and Christian thought, since nothing analogous to the biblical concept of repentance and conversion was known to the Greeks.” To understand what metanoeo and epistrepho (G1994) meant to early Christians, we need to look back at the Hebrew words expressing the same concepts.

Once again, we have two words that can be translated into English as “repent.” One of those, nacham (H5162) is typically only used of God “repenting” in the sense of “relenting or changing,” like He did when he delayed Nineveh’s destruction in response to their repentance (Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament [TWOT] entry 1344). In that story of Nineveh, we also see the Hebrew word more commonly used for human repentance, shub (H7725).

Jonah began to enter into the city a day’s journey, and he cried out, and said, “In forty days, Nineveh will be overthrown!”

The people of Nineveh believed God; and they proclaimed a fast, and put on sackcloth, from their greatest even to their least. The news reached the king of Nineveh, and he arose from his throne, and took off his royal robe, covered himself with sackcloth, and sat in ashes. He made a proclamation and published through Nineveh by the decree of the king and his nobles, saying, “Let neither man nor animal, herd nor flock, taste anything; let them not feed, nor drink water; but let them be covered with sackcloth, both man and animal, and let them cry mightily to God. Yes, let them turn (shub) everyone from his evil way, and from the violence that is in his hands. Who knows whether God will not turn (shub) and relent (nacham), and turn (shub) away from his fierce anger, so that we might not perish?”

God saw their works, that they turned (shub) from their evil way. God relented (nacham) of the disaster which he said he would do to them, and he didn’t do it.

Jonah 3:4-10, WEB

The basic meaning of shub is to turn or return. It is a Hebrew verb used frequently; “over 1050 times” in the Old Testament. While the Hebrew writers use many word pictures to describe repentance, all “are subsumed and summarized by this one verb shub. For better than any other verb is combines in itself the two requisites of repentance: to turn from evil and to turn to the good” (TWOT 2340). Like the Greek words that would later represent the same concept, Hebrew notions of repentance include both regret and turning away from sin and turning toward God. There’s always a sense of change; the verb shub is so connected with turning and change that it is even used of physical movement and coming back to a people or location (TWOT 2340).

The word shub is particularly important in it’s relation to “the covenant community’s return to God,” and one scholar concludes “there are a total of 164 uses of shub in a covenantal context” (TWOT 2340). Covenants are the way that God makes formal relationships with people; if we’re truly following God then we have made a covenant commitment to Him. Under the terms of a covenant, both parties involved have rights and responsibilities. In relation to repentance, both God and humanity have a role to play. The person repenting goes “beyond contrition and sorrow to a conscious decision of turning to God,” God freely extends His sovereign mercy, and then we continue in a commitment that involves “repudiation of all sin and affirmation of God’s total will or one’s life” (TWOT 2340). That concept is found in the Old Covenant, and is reinforced in the New Covenant (Acts 3:19; 26:17-20; 1 Thes. 1:9).

Trumpet Blasts As A Call to Return

In last week’s post, I talked about observing the Day of Trumpets (Yom Teruah). It is one of God’s special holy days, which He commands His covenant people to keep. It is a Sabbath day of complete rest, a day God calls His people to gather together, and “a memorial announced by loud horn blasts” (Lev. 23:24, WEB); “it is a day of blowing trumpets for you” (Num. 29:1, WEB). We traditionally say that in the New Covenant, the Day of Trumpets pictures the second coming of Jesus Christ, which will be heralded by trumpet blasts (1 Thes. 4:15-18).

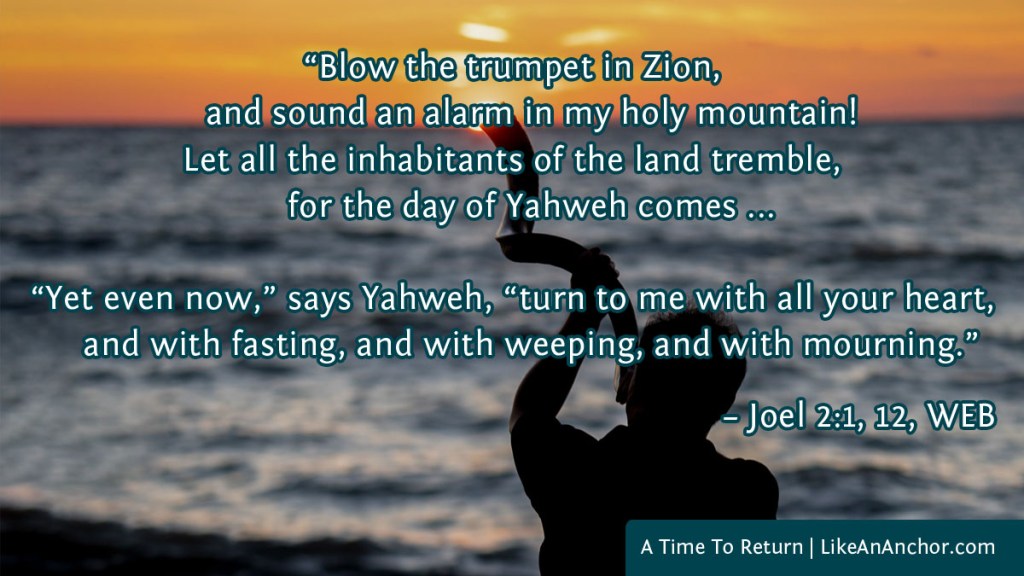

We can also see the trumpet blasts as a call to alert us today of the need to return to God. In Jewish tradition, the Sabbath day that falls between Day of Trumpets and Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur) is called Shabbat Shuvah, the Sabbath of Return. As we just learned, shuvah/shub is the Hebrew word for repentance. As we move from Day of Trumpets to Day of Atonement, repentance should be on our minds.

Blow the trumpet in Zion,

Joel 2:1-2, WEB

and sound an alarm in my holy mountain!

Let all the inhabitants of the land tremble,

for the day of Yahweh comes,

for it is close at hand:

A day of darkness and gloominess,

a day of clouds and thick darkness.

As the dawn spreading on the mountains,

a great and strong people;

there has never been the like,

neither will there be any more after them,

even to the years of many generations.

As Joel warns, the time before Jesu’s return (the day of Yahweh, or day of the Lord) will be a dark time for the world as a whole. The world is getting worse and worse as His return draws nearer, and Revelation reveals it’s only going to get even worse (like during the soundings of the seven trumpets given to angels; Rev. 8-11). When contemplating the coming of this day, Peter asks a pertinent question: “since all these things will be destroyed like this, what kind of people ought you to be in holy living and godliness?” (2 Pet. 3:11, WEB). He answers by saying that since we look for Jesus’s return, we should “be diligent to be found in peace, without defect and blameless in his sight” and “grow in the grace and knowledge of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ” (2 Pet. 3:14, 18 WEB). Joel records a similar warning to turn back to following God faithfully.

Yahweh thunders his voice before his army;

Joel 2:11-16, WEB

for his forces are very great;

for he is strong who obeys his command;

for the day of Yahweh is great and very awesome,

and who can endure it?

“Yet even now,” says Yahweh, “turn to me with all your heart,

and with fasting, and with weeping, and with mourning.”

Tear your heart, and not your garments,

and turn to Yahweh, your God;

for he is gracious and merciful,

slow to anger, and abundant in loving kindness,

and relents from sending calamity.

Who knows? He may turn and relent,

and leave a blessing behind him,

even a meal offering and a drink offering to Yahweh, your God.

Blow the trumpet in Zion!

Sanctify a fast.

Call a solemn assembly.

Gather the people.

Sanctify the assembly.

This year, we will observe the Day of Atonement on September 25, 2023. This is a solemn holy day when God commands us to rest completely and “afflict your souls” (traditionally understood to mean fasting). Reading Joel, I can’t help but notice that the trumpet blasts warning that the Messiah’s return is coming closer and closer also call us to fast and repent. God and the prophet Joel call out to readers, saying, “turn (shub) to Yahweh, your God!”

All of us are getting closer every day either to the end of our lives or to Jesus Christ’s return. One way or another, we have a limited time here on this earth. Keeping the Day of Trumpets and Day of Atonement remind us of that. They also remind us of the wonderful things the Messiah has done and is doing for His people. Because of Jesus’s atoning sacrifice, God graciously removes our sins when we repent, turning our lives around and (re)committing to following Him faithfully. We need that reminder of His awesome mercy, of our total dependence on Him, and of His promise to return and set things on this earth right.

Featured image by Pearl from Lightstock

Song Recommendation: “All You’ve Ever Wanted” by Casting Crowns