In the lady’s scripture writing group that I’m part of in our local church congregation, the theme for January is “Wait on the Lord.” When I was writing a scripture earlier this month, I noticed that some translations of Psalm 31:24 used the word “hope” and others used the word “wait.” Those are two very different words in English, so I wondered how they could be so connected in Hebrew that “hope” is just as good of a translation for the word as “wait.”

I’ve heard quite a few native English speakers describe Hebrew as weird and frustrating. How can you have words that mean completely opposite things depending on the context? It makes no sense! But the more I study the Bible and read about Hebrew language and thought, the more I appreciate that Hebrew isn’t a more limited language than English. It’s just a very different kind of language. Lois Tverberg compares languages to painting styles–Hebrew uses broader brush strokes and a more limited color pallet (i.e. number of words; about 8,000 for Hebrew) while English uses a fine-tipped brush, different colors, and more colors (there are about 100,000 English words). Language shapes so much of how we think, so if we want to understand the thought process of the people God used to write the Bible, it helps to learn more about the languages they used.

A Look At Hebrew Language

Be strong, and let your heart take courage,

Psalm 31:24, WEB

all you who hope in Yahweh.

Be strong and confident,

Psalm 31:24, NET

all you who wait on the Lord.

In English, these different translations make it seem like the verse could mean two completely different things. For English speakers, hoping in Yahweh isn’t at all the same thing as waiting on the Lord. We think of hope as a feeling of expectation, desire, or trust (Oxford Languages via Google). Waiting is something we do until something else happens, a staying in place or delaying action (Oxford Languages via Google). If you’re excited about the thing you’re waiting on or trust that it could happen you might feel hope, but they’re not necessarily connected.

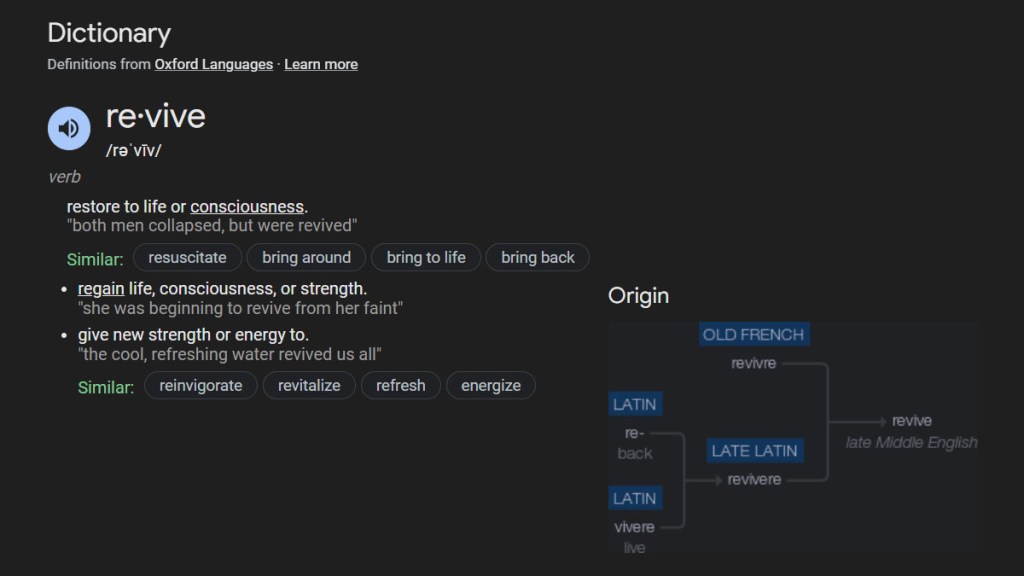

The Hebrew word translated either “hope in” or “wait on” is yachel/yahal (יָחַל, H3176). It’s a verb (action word) that is primarily translated “hope” in the KJV, but also “wait,” “trust,” and “tarry.” The Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (TWOT) states that the word carries “the idea of ‘tarrying’ and ‘confident expectation, trust'” as well as “hope” (TWOT entry 859). They explain the hope-wait connection like this:

“yahal is used of ‘expectation, hope’ which for the believer is closely linked with ‘faith, trust’ and results in ‘patient waiting.’ … This yahal ‘hope’ is not a pacifying wish of the imagination which drowns out troubles, nor is it uncertain (as in the Greek concept), but rather yahal ‘hope’ is the solid ground of expectation for the righteous.”

TWOT entry 859

Yahal “is a close synonym to batah ‘trust’ and qawa ‘wait for, hope for'” (TWOT 859). We won’t look at batah in this post, but most of the other verses I’ve been writing this month translate “wait” from the word qavah or qawa (קָוָה, H6960). This word “means to wait or to look for with eager expectation” (TWOT 1994). Qavah has to do with waiting in faith, trusting in God, hope for the future. The root verb qawa is most often translated “wait” and “look for” in the KJV. It’s the derivative noun tiqvah that’s usually translated “hope” or “expectation.” There are also several other words that can be translated “wait.” Some of these are also translated “hope,” including sabar/shabar (H7663: “to inspect, examine, wait, hope, wait upon [BDB]) and others without the hope connotation, such as chakah (H2442: “wait, wait for, await” [BDB]). We won’t dive into all these different words in this post, but I wanted to bring them up to demonstrate the wait/hope connection is woven throughout the language.

Confident Expectation

Once I started thinking about “wait” and “hope” as being connected, it’s almost impossible not to see it. The first time the word yahal appears in the Bible is in Genesis 8:12. This is after the flood, while Noah, his family, and all the animals are still on the ark.

At the end of forty days, Noah opened the window of the ship which he had made, and he sent out a raven. It went back and forth, until the waters were dried up from the earth. He himself sent out a dove to see if the waters were abated from the surface of the ground, but the dove found no place to rest her foot, and she returned into the ship to him, for the waters were on the surface of the whole earth. He put out his hand, and took her, and brought her to him into the ship. He waited yet another seven days; and again he sent the dove out of the ship. The dove came back to him at evening and, behold, in her mouth was a freshly plucked olive leaf. So Noah knew that the waters were abated from the earth. He waited yet another seven days, and sent out the dove; and she didn’t return to him any more.

Genesis 8:6-14, WEB

There are two times in this passage where an English translation says, “He waited.” The first time, the Hebrew word is chûl/chı̂yl (H2342): “to twist, whirl, dance, writhe, fear, tremble, travail, be in anguish, be pained” (BDB definition). Clearly, this is not a hopeful sort of waiting. It’s an anxious waiting. But then, after the dove comes back with “a freshly plucked olive leaf” so that Noah knew the waters were starting to dry up, the type of waiting changes. This time, “he yahal yet another seven days.” Now, Noah had a reason to hope and the way that he waited changed.

Unfortunately, there isn’t an English word that would capture wait/hope as a dual meaning. Translators either have to pick one or the other, or replace the single word with a whole phrase that means something similar. The Amplified Bible translation (AMP) does this for yahal sometimes (though not in Genesis 8). AMP renders Psalm 31:24 as “Be strong and let your hearts take courage, All you who wait for and confidently expect the Lord.” That’s what Noah was doing, at least once he’d seen evidence that the earth was growing back after the flood.

God Shows Up

When studying a Hebrew word, I often like to focus on how the word is used in Psalms because those songs are so much about the relationship between people and God. Relationships lie at the heart of Christianity, and I find it particularly insightful to look at how people of faith used certain words when recording their feelings, thoughts, and worship.

We see yahal in 19 verses in Psalms, including some that describe a situation where it doesn’t seem like “hope” is the expected response. While “hope” is the traditional default translation, the NET translators maintain that “to wait” is the “base meaning” of yahal and whether “the person waiting is hopeful or expectant” depends on context (footnote on Ps. 42:5). I wonder, though, if the authors meant there to be some hints of hope even in the ones where it doesn’t seem (to us) to fit the context. After all, there are other words the authors could have used for “wait.”

Behold, Yahweh’s eye is on those who fear him,

Psalm 33:18-22, WEB

on those who hope in his loving kindness,

to deliver their soul from death,

to keep them alive in famine.

Our soul has waited for Yahweh.

He is our help and our shield.

For our heart rejoices in him,

because we have trusted in his holy name.

Let your loving kindness be on us, Yahweh,

since we have hoped in you.

Here, “hope” is translated from yahal and “waited” from chakah (the NET translates all of them “wait”). Now, this one (Psalm 33) is a psalm of praise, and it makes sense to our minds that we’d see “hope” in this context. But we also see “I hope in you, Yahweh” (Ps. 38:15) in a psalm that begins with God’s indignation and wrath (Psalm 38) and the instruction “hope in” or “wait for” God (Ps. 42:5, 11; 43:5) when suffering despair and persecution (Psalms 42; 43). Those are the times when we need hope the most. And one of the reasons that we can have hope that’s a “confident expectation” rather than something uncertain is because God has showed up so many other times when we (and other people of faith) waited for Him.

A Sure, Certain Hope

One of God’s promises that we’re still waiting on is that He will resurrect all His faithful followers from the dead. That’s not something that’s happened yet. Like so many of God’s promises, some people (even in the 1st century, right after Jesus’s life, death, and resurrection) say that it won’t happen. But, as Paul points out, God’s track record proves that He can follow-through on His promises.

Now if Christ is being preached as raised from the dead, how can some of you say there is no resurrection of the dead? But if there is no resurrection of the dead, then not even Christ has been raised. And if Christ has not been raised, then our preaching is futile and your faith is empty. … And if Christ has not been raised, your faith is useless; you are still in your sins. Furthermore, those who have fallen asleep in Christ have also perished. For if only in this life we have hope in Christ, we should be pitied more than anyone. But now Christ has been raised from the dead, the firstfruits of those who have fallen asleep.

1 Corinthians 15:12-14, 17-20, NET

For Paul, the fact that God the Father raised Jesus Christ from the dead proves that He will raise “those who have fallen asleep in Christ” as well. Our hope in the resurrection is a confident expectation because there’s already proof that God can do it, just like Noah’s hope that the water would recede became confident when he saw evidence of plant life on the earth.

You are my hiding place and my shield.

Psalm 119:114, 116, WEB

I hope (yachal) in your word. …

Uphold me according to your word, that I may live.

Let me not be ashamed of my hope (seber).

God’s word contains many promises that we can read about. They’re backed up by His proven character, and because He is trustworthy we know that when we wait hopefully, He’s not going to disappoint us or make it so that we’d be ashamed of following Him.

Being therefore justified by faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ; through whom we also have our access by faith into this grace in which we stand. We rejoice in hope of the glory of God. Not only this, but we also rejoice in our sufferings, knowing that suffering produces perseverance; and perseverance, proven character; and proven character, hope: and hope doesn’t disappoint us, because God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit who was given to us. For while we were yet weak, at the right time Christ died for the ungodly.

Romans 5:1-6, WEB

Just reading through the Bible and observing how people talk about hope, we can see that it’s connected with confident expectation and it’s something that Biblical writers treat as certain as long as it’s pointed towards God. Studying the Hebrew language a little bit more and learning that wait and hope are so closely connected in that language can help us understand on a deeper level how the Biblical writers understood hope and waiting on God. It can teach us about both the Old Testament, which was written in Hebrew, and the New Testament, which was written by Jewish people who were deeply influenced by their linguistic history. And that can help us hold on to hope today when we’re waiting on God to do something in our lives or fulfill His promises.

Featured image by Ben White

Song Recommendation: “Trust His Hands” by Jean Watson