I’ve been thinking about covenants a lot lately, especially the topic of which covenants transfer to us today and how that happens. I think of this as the topic of “inheriting covenants,” the title of a blog post I wrote way back in 2016. When I realized how long ago I wrote that post, I wanted to revisit the topic. As we grow in our walk with God, we should gain a deeper appreciation and understanding of His word. It’s good to go back sometimes and revisit topics we thought we understood well. As Paul said, “If someone thinks he knows something, he does not yet know to the degree that he needs to know” (1 Cor. 8:2, NET). There’s so much depth to God’s word; so much to learn as we grow.

Defining Covenants

Let’s start with the basics. In Hebrew, the word for “covenant” is berith (H1285). In Greek, for the New Testament, the word is diatheke (G1242). These words don’t mean exactly the same thing, and so it can be challenging for us today to figure out what the Biblical writers meant by covenants and how they worked. Also, most of our lives aren’t based on covenants today; in the U.S., I’ve rarely heard that word used outside of a religious context. We need to do some linguistic and historical research to understand covenants, which are so important to the Biblical world and God’s ongoing relationships with humanity.

The Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (TWOT) notes that “Apart from blood ties the covenant was the way people of the ancient world formed wider relationships with each other” (entry 282a). Covenants have to do with establishing relationship. They were binding agreements between two parties that people in the ancient world took very seriously; “There is no firmer guarantee of legal security peace or personal loyalty than the covenant” (Behm, qtd. in TWOT). When God made a covenant with His people, we was binding Himself in relationship to them in the most reliable way possible. Like other covenants, the ones between God and humanity include both expectations and promises. Covenant documents between people survive to the present day, and the format of them has many similarities with God’s Ten Commandments and the book of Deuteronomy (Klein, ref. in TWOT).

In Greek, diatheke means testament, as in “the last disposition which one makes of his earthly possessions after his death,” or a covenant agreement (Thayer). According to Spiros Zodhiates, dispensation/testament is always the usage in classical Greek (The Complete WordStudy Dictionary of the New Testament, entry 1242). New Testament writers picked this word to use for covenants. That might seem odd at first, but Zodhiates proposes a definition of covenant that covers both the unilateral enactment of diatheke and the established relationship of berith. He writes that what we describe as a covenant “is a divine order or agreement which is established without any human cooperation and springing from the choice of God Himself whose will and determination account for both its origin and its character” (entry G1242, section IV).

Indeed, we always see God as the initiator of covenants and, by necessity, the relationship established by a covenant with God is always one where He is the superior party. God calls us His friends, but that is a gracious choice on His part; we are by no means His equals nor can we make demands of Him. We either choose to accept the covenants He offers, or we reject relationship with Him. We don’t get the chance to insert our own demands into the covenant; we trust that we’re more than adequately protected and provided for by His promises.

Key Covenants

There are four main covenants that God made with human beings that are recorded in the Old Testament writings: the Noahic Covenant, the Abrahamic Covenant, the Sinai Covenant, and the Davidic Covenant. There are other covenants mentioned, but those are the big ones. The BibleProject has a great summary of these on YouTube:

With the exception of the Noahic Covenant, the covenants God made with people included expectations for God’s human covenant partners. God kept up His covenant promises, but people broke the covenants with God. That put us under a death-penalty; a curse (Rom. 3:23; 5:12; Gal. 3:10). Then Jesus came along. As a human being, He was a physical descendant of Abraham, an Israelite heir of the covenants with God, and a man in the lineage of David (Acts 2:29-31). He was born into the physical position of an heir to all these key covenants. He also came as God in the flesh, so He can see covenants from both sides and keep covenant perfectly both as God and human.

Prior to Jesus Christ coming to this earth, all except the Noahic Covenant were linked to Abraham’s descendants. The Sinai Covenant was with all of physical Israel and included a fuller revelation of God’s law and expectations. The Davidic covenant was more specific, applying to one line of the tribe of Judah. It was possible for a stranger to join themselves to Israel and become part of the Abrahamic and Sinai Covenants with God, as Rahab and Ruth did, but it was apparently quite rare and more often than not was discussed in a prophetic context (Is. 56:6-7).

That also changed with Jesus’s coming. In the New Testament, Paul writes to Gentile believers that they were “alienated from the citizenship of Israel and strangers to the covenants of promise, having no hope and without God in the world” until the time of their conversion. They were not previously heirs to the covenants, “But now in Christ Jesus you who used to be far away have been brought near by the blood of Christ” (Eph. 2:12-13, NET). This is a fulfillment of a promise that God delivered through His prophets; a promise to make a better New Covenant with the people of Israel and the spiritual descendants of Abraham.

A Question of Inheritance

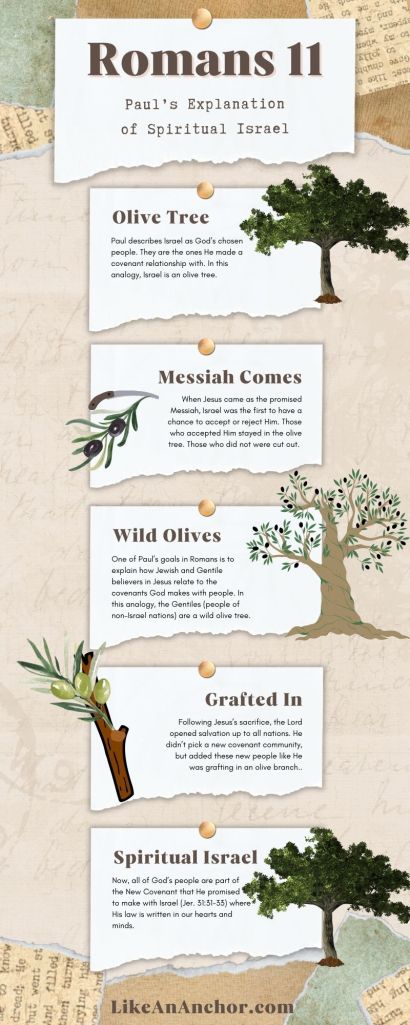

I usually go to Romans when I want to discuss covenants, which is where we were a couple weeks ago when I shared an infographic illustrating how all God’s people become spiritual Israel. Today, though, we’re going to spend some time in Galatians.

In this letter, Paul writes to a group of churches with the expressed purpose of countering distorted gospels (Gal. 1:6-8). He wants to ensure that they follow the pure gospel that he receive, not some distortion arising from human reasoning (Gal. 1:1, 11-12, 15-24). That’s the perspective Paul’s coming from when he discusses covenants in this letter.

It appears that the Galatian believers had been deceived by a person or group who told them they needed to keep the whole Jewish law in order to be saved. The Galatians were worried that the male believers needed to be circumcised, that they had to keep the whole Old Covenant law, and that they additionally had to keep Jewish additions to God’s law. Paul reminds them that it is Jesus’s faithfulness that brings us righteousness and justification, not our own efforts. That doesn’t mean we break God’s law; Christ in us most certainly does not encourage sin. But He also didn’t save us and give us the Spirit so that we could then save ourselves by our own efforts. Rather, we’re following the example of Abraham.

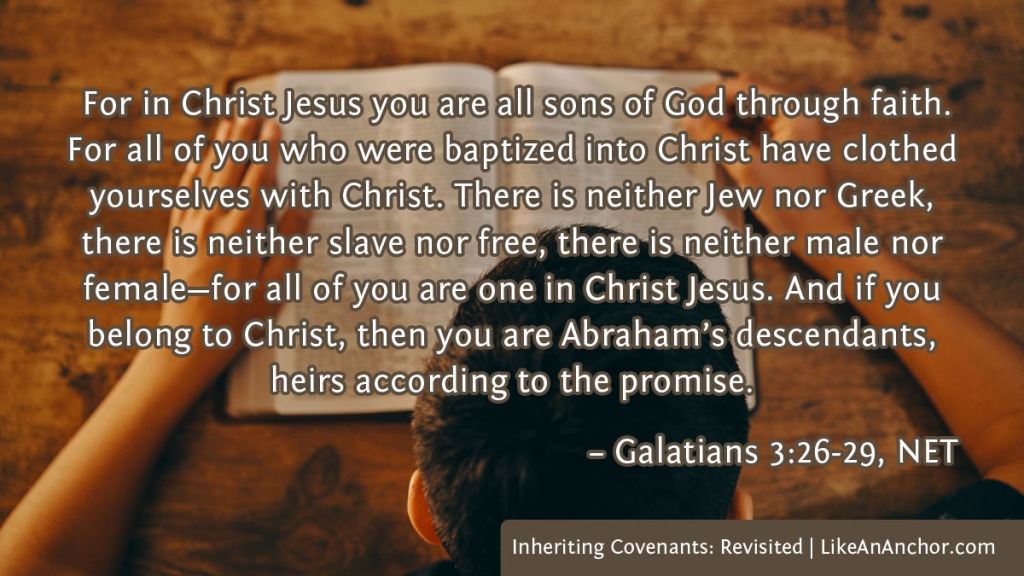

Just as Abraham believed God, and it was credited to him as righteousness, so then, understand that those who believe are the sons of Abraham. And the scripture, foreseeing that God would justify the Gentiles by faith, proclaimed the gospel to Abraham ahead of time, saying, “All the nations will be blessed in you.” So then those who believe are blessed along with Abraham the believer.

Galatians 3:6-9, NET (bolt italics mark quotes from the Old Testament)

Here, Paul quotes from the record in Genesis of God cutting a covenant with Abraham (Gen. 15). This covenant is one of inheritance and blessing. We learn more about it in Genesis 17 and 18, which Paul also quotes. If you read that section, you’ll notice that God’s covenant with Abraham included people following the Lord’s way and doing what is right. But, as Paul emphasizes, the promises come to Abraham and his descendants because God is faithful, not because they kept the Law that God later shared as part of the Sinai Covenant or because they observed Jewish traditions added later.

God does want people to follow His law (it defines sin and, since sin is not consistent with God’s character, it damages relationships between us and Him). But God also knows that all people sin. It is very, very good for us that He upholds His part of covenants even when people aren’t faithful, because one of those covenant promises was that God would send Jesus as the Messiah. That’s how we inherit the Abrahamic Covenant promises: through Jesus Christ.

Brothers and sisters, I offer an example from everyday life: When a covenant has been ratified, even though it is only a human contract, no one can set it aside or add anything to it. Now the promises were spoken to Abraham and to his descendant. Scripture does not say, “and to the descendants,” referring to many, but “and to your descendant,” referring to one, who is Christ. What I am saying is this: The law that came 430 years later does not cancel a covenant previously ratified by God, so as to invalidate the promise. For if the inheritance is based on the law, it is no longer based on the promise, but God graciously gave it to Abraham through the promise.

Galatians 3:15-18, NET (bolt italics mark quotes from the Old Testament)

A few verses later, Paul says that the Law was “added because of transgressions, until the arrival of the descendant to whom the promise had been made” (Gal. 3:19, NET). He also says the law was a guard to keep us safe and a “tutor to bring us to Christ, that we might be justified by faith” (Gal. 3:24, WEB). The law defines sin for us and reveals the penalties for breaking God’s covenant law. As transgressors of the covenant, we deserved to inherit the curses contained in the covenanting words (Deut. 11:26-32; 27:1-28:68). The only one who perfectly kept God’s covenant was Jesus Christ, and so He’s the only one who truly deserved to inherit all the promises. When He died, He “willed” those promises to us. We inherit the Abrahamic Covenant alongside Him, and through Him we’re brought into the New Covenant that God long ago promised would replace the Old (Sinai) Covenant (Jer. 31:31-34; Heb. 8).

Promises Through Jesus

I find it so fascinating that the New Testament writers use the fact that the Greek word for covenant also means last will and testament to connect the idea of covenant inheritance to our adoption as God’s children (Gal. 3:26-4:7; Rom. 8:14-17). The author of Hebrews spends quite a bit of time explaining this concept, particularly the transition from Old to New Covenant.

And so he [Jesus] is the mediator of a new covenant, so that those who are called may receive the eternal inheritance he has promised, since he died to set them free from the violations committed under the first covenant. For where there is a will, the death of the one who made it must be proven. For a will takes effect only at death, since it carries no force while the one who made it is alive.

Hebrews 9:15-17

As the Word of God, Jesus is (almost certainly) the God-being who delivered the first covenants in the Old Testament. Then, as the original testator, He died so we can be freed from the Old Covenant and join Him in a New Covenant (Jer. 31:32-34; Rom 7:1-4). At the same time, as a human heir to all the covenants (and the only person who kept humanity’s side of the covenant bargain, since He never sinned), Jesus died to take on Himself the penalty we earned for breaking the covenant, purify us with His blood, and bring us into a new covenant (Heb. 9:18-28). Yet another layer is that He inherits all the promises, wills them to us at His death, then rises again to inherit as well (Eph. 1:3-21).

We were also assigned an inheritance in him, having been foreordained according to the purpose of him who does all things after the counsel of his will, to the end that we should be to the praise of his glory, we who had before hoped in Christ. …

For this cause I also … don’t cease to give thanks for you, making mention of you in my prayers, that the God of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of glory, may give to you a spirit of wisdom and revelation in the knowledge of him, having the eyes of your hearts enlightened, that you may know what is the hope of his calling, and what are the riches of the glory of his inheritance in the saints, and what is the exceeding greatness of his power toward us who believe, according to that working of the strength of his might which he worked in Christ, when he raised him from the dead

Ephesians 1:11-12, 15-20, WEB

It’s amazing to me that God invites us to be covenant partners with Him and participate in the relationships that He’s been building with humanity since the world began (the word “covenant” isn’t used in the creation story, but the words of His promises to Adam and Eve are covenant-like, and some call it the Adamic Covenant). People often say that God wants a personal relationship with you, and covenants are the way that the Bible describes that relationship. They’re so important to understanding our role in God’s plan and His family, and I don’t think we talk about them enough. The more deeply and completely we understand covenants, the better we’ll understand God and the relationship He wants to have with us.

Featured image by falco from Pixabay

Song Recommendation: “Crucified with Christ” by Phillips Craig Dean