Extra post this week because I’m so excited about the Women’s Classic Literature Event hosted by The Classics Club. I’ve read many great classics written by women, and look forward to discovering more over the next year. Even if you’re not part of the Classics Club reading challenge, you’re still welcome to jump on board with this event using the #ccwomenclassics hashtag to share what you’re reading.

A Survey for the Women’s Classic Literature Event

Introduce yourself. Tell us what you are most looking forward to in this event.

- As a female writer, I’m all for reading literature written by women. I studied English at The Ohio State University, and my undergraduate research project focused on Frances Burney and Mary Wollstonecraft. For this event, I’m most looking forward to seeing my fellow readers discover amazing classics by women writers, and then gathering suggestions from them for my own “to-read” list.

Have you read many classics by women? Why or why not?

- I have read quite a few. We picked out some for my high school curriculum (homeschooled), then in college I was blessed to take classes from English professors who made sure to teach fine books written by both men and women.

Pick a classic female writer you can’t wait to read for the event, & list her date of birth, her place of birth, and the title of one of her most famous works.

- Mary Shelley, born 30 August 1797 in London, England. I’ve read some of her mother’s writings, but nothing by her. Frankenstein is Mary Shelley’s most famous work.

Favorite classic heroine? (Why? Who wrote her?)

- Jane Eyre, written by Charlotte Bronte. I love first-person narrative when it’s well written, and Bronte makes Jane a spectacular narrator. She’s a strong, clever woman and I admire her moral strength and unabashed living out of her Christian faith. (Bonus: Jane’s a fictional example of my INFJ personality type.)

Recommend three books by classic female writers to get people started in this event. (Again, skip over this if you prefer not to answer.)

- Evelina by Frances Burney. I did my undergraduate research project on Burney, and highly recommend her work to fans of Jane Austen. Evelina is the shortest and most manageable of her novels, so I suggest trying that one out before jumping into the 900+ page Cecelia or Camilla.

- Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte. If you haven’t read this famous classic yet, I hope you will. It’s one of my favorite books of all time, and I love the characters.

- North and South by Elizabeth Gaskell. I love this book and the BBC adaptation staring Daniela Denby-Ashe and Richard Armitage. The casting is perfect, and my only quibble with the plot adaptation is the ending/proposal scene … but no more on that for fear of spoilers.

Will you be joining us for this event immediately, or will you wait until the new year starts?

- I’ll probably write about Tenant of Wildfell Hall in November or December.

Do you plan to read as inspiration pulls, or will you make out a preset list?

- I’ll pull from the women writers already on my Classics Club list, and maybe add a few more as inspiration strikes.

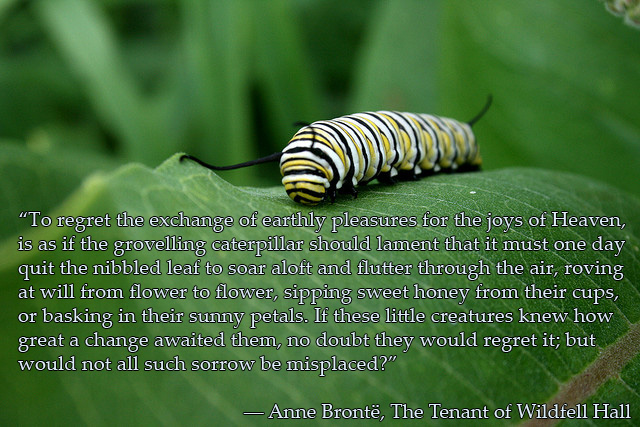

Share a quote you love by a classic female author — even if you haven’t read the book yet.

- Here’s one I took note of when reading Anne Bronte’s Tenant of Wildfell Hall.

I’m not actually all that far behind on my reading for

I’m not actually all that far behind on my reading for

This is one of those rare books where the last line sums-up my feelings about the rest of the story.

This is one of those rare books where the last line sums-up my feelings about the rest of the story.