If you’re reading this when it posts, then today (Sept. 30, 2023), is the first day of the Feast of Tabernacles (Sukkot). As we made preparations to keep this Feast, I’ve been thinking about a book of the Bible that, at first glance, you might think doesn’t have much to do with the holy days. Usually when talking about God’s holy times, we turn to some place like Leviticus 23, which outlines all the days God says are holy to Him. This year, though, I’ve been thinking about Romans.

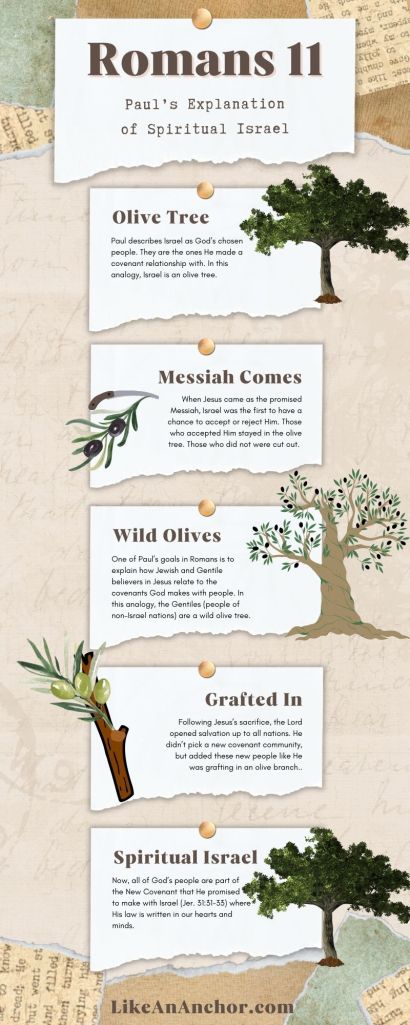

I’m sure I’ve mentioned before that Paul’s letter to the Romans is one of my favorite books in the Bible. There’s so much depth to it; I think I could spend a lifetime studying it and not fully understand everything. While reading Romans 10 and 11 a few weeks ago, I sketched out some notes trying to visualize the olive tree grafting analogy that Paul uses when discussing how New Covenant Christians and Gentile believers (those who were not ethnically part of Israel) become part of God’s community of faith, and what happened to the Jewish people who did not accept Jesus as the Messiah. Earlier, I also sketched out a chart trying to illustrate the different ways that Paul speaks to Jewish and Gentile converts about God’s law. I turned one into an infographic and one into a sort of flowchart. These visualizations helped me, and I’m sharing them in hope they might be useful to others as well.

Two Paths to Get to Christ

Often, I think Christians make the mistake of thinking that Christianity was a new religion started by Jesus and that the Jews today are still keeping the faith described in the Old Testament. What we ought to realize is that Jesus came as the next step in God’s plan for His people. He was the promised Messiah, and those who accepted Him continued along the path God laid out for His people from Genesis onward. Assuming you believe that Jesus is the Messiah, then those who didn’t believe in Him are the ones who broke off and went a different direction. That’s what Paul is addressing in this section of Romans.

Brothers and sisters, my heart’s desire and prayer to God on behalf of my fellow Israelites is for their salvation. For I can testify that they are zealous for God, but their zeal is not in line with the truth. For ignoring the righteousness that comes from God, and seeking instead to establish their own righteousness, they did not submit to God’s righteousness. For Christ is the end of the law, with the result that there is righteousness for everyone who believes.

Romans 10:1-4, NET

Paul was a Jewish man who had zeal for God that originally didn’t line up with the truth. He persecuted Christians at first, but when Jesus dramatically revealed Himself to Paul as the Messiah, Paul aligned His zeal with God’s truth. After that, he wanted all of his fellow Israelites to have a similar awakening. At this point, rather than aligning themselves with God’s truth, the way that they were trying to follow His law involved doing things their own way. Christ brings an end to trying to keep the law as a way to establish your own righteousness.

The Greek word for “end” here can mean the end or completion point, but it also means “the end to which all things relate, the aim, purpose” (Thayer, G5056, 1d). Now, remember that when we’re interpreting Paul we need to keep in mind that, as a faithful apostle, he would not contradict one of Jesus’s teachings. Jesus said, “Do not think that I have come to abolish the law or the prophets. I have not come to abolish these things but to fulfill them” (Matt. 5:17, NET). Here, He’s saying that He came “to fulfil, i.e. to cause God’s will (as made known in the law) to be obeyed as it should be, and God’s promises (given through the prophets) to receive fulfilment” (Thayer, G4137, 2c3). Therefore, Paul is not saying that Jesus got rid of the law. He’s pointing out that we don’t become righteous by keeping the law.

Paul taught both Jewish and Gentile Christians. These two groups had different relationships to the law of God as they came into the church. For Jewish Christians, “the law was our schoolmaster to bring us unto Christ, that we might be justified by faith” (Gal. 3:24, KJV). For Gentile Christians (particularly those who weren’t already “God fearers” who’d aligned themselves with the Jewish faith), they came to Jesus by faith first and learned about God’s laws afterwards. You’ll often see Paul telling his Jewish readers that it’s important to keep God’s law on a heart level now and to understand they can’t make themselves righteous, and teaching his Gentile readers to obey God but not accept extra Jewish traditions they’d added on top of the law.

For Moses writes about the righteousness that is by the law: “The one who does these things will live by them.” But the righteousness that is by faith says … “The word is near you, in your mouth and in your heart” (that is, the word of faith that we preach), because if you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved. For with the heart one believes and thus has righteousness and with the mouth one confesses and thus has salvation. For the scripture says, “Everyone who believes in him will not be put to shame.” For there is no distinction between the Jew and the Greek, for the same Lord is Lord of all, who richly blesses all who call on him. For everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.

Romans 10:5-6, 8-13 (bold italics in original to mark OT quotes)

Paul uses quotes from the Old Testament to support his thesis that Jewish and Gentle Christians are part of the same spiritual family. God wants all His people in community together, joined into one covenant relationship with Him. For many of the Gentiles, this is the first time they’ve been in covenant with God. For the Jewish believers, the New Covenant was a promise contained in the Old Covenant. Whichever way they came into the family, they’re now both part of that New Covenant with God.

Grown or Grafted into One Tree

So I ask, God has not rejected his people, has he? Absolutely not! For I too am an Israelite, a descendant of Abraham, from the tribe of Benjamin. God has not rejected his people whom he foreknew! Do you not know what the scripture says about Elijah, how he pleads with God against Israel? “Lord, they have killed your prophets, they have demolished your altars; I alone am left and they are seeking my life!”

But what was the divine response to him? “I have kept for myself seven thousand people who have not bent the knee to Baal.” So in the same way at the present time there is a remnant chosen by grace. And if it is by grace, it is no longer by works, otherwise grace would no longer be grace. What then? Israel failed to obtain what it was diligently seeking, but the elect obtained it. …

I ask then, they did not stumble into an irrevocable fall, did they? Absolutely not! But by their transgression salvation has come to the Gentiles, to make Israel jealous … Now I am speaking to you Gentiles. Seeing that I am an apostle to the Gentiles, I magnify my ministry, if somehow I could provoke my people to jealousy and save some of them. For if their rejection is the reconciliation of the world, what will their acceptance be but life from the dead?

Romans 11:1-7, 11, 13-15, NET (bold italics in original to mark OT quotes)

Through His prophets, God revealed that He always intended to open up salvation to all nations after the Messiah came. Even before that, He allowed people from non-Israelite nations to join the covenant community if they really wanted. As Paul was writing, though, this broad preaching of the good news to all the nations was a new and exciting thing.

This doesn’t mean God started a brand new family/community, though. He transitioned His family to a new and better covenant, and welcomed new members in. Those who didn’t want to come with Him into the New Covenant got cut out of the community (at least for a little while). I find this easier to wrap my head around with a visualization. If you’re subscribed to my newsletter, you’ve already seen this infographic. I sent it out on Wednesday to give newsletter readers a sneak peak and to ask for feedback on the design.

The Things We Do In God’s Family

One of the things that stood out to me when I was reading Misreading Scripture with Individualist Eyes by E. Randolph Richards and Richard James was the way they described Paul’s letters discussing Jewish and Gentile believers. One of the things Paul is doing when writing to believers, including in his Romans letter, is telling them they are part of a new community. In collectivist cultures, people get their identity from a group. Before conversion, Jews and Gentiles were part of different communities with different expectations, beliefs, and codes of conduct. Now, though, they are part of God’s covenant community.

When we’re in God’s community as part of His family, there are certain expectations that come with that. For example, we’re expected to treat God’s name with respect and honor Him with our words and conduct. He expects us to come to Him when we need help rather than turn to something else first. We’re to love the Father and Jesus, and Jesus said if we love Him then we will keep His commandments. Most Christians today already know that this includes the 10 Commandments, but those aren’t the only aspects of God’s law that transfer to the New Covenant. They’re more of a summary.

As already mentioned, Jesus said He came to fill the law and the prophets to their fullest extent, not to abolish them (Matt. 5:17) In some ways, more is expected of us in the New Covenant rather than less. We don’t need to do all the sacrifices since “by one offering he [Jesus] has perfected forever those who are being sanctified” (Heb. 10:14, WEB), but we are expected to obey the law on a heart level and not just a letter level (Matt. 5:17-48). God’s laws and commands describe the things that we do as part of God’s family; the things that He expects from people who have a covenant relationship with Him. His Sabbaths and Holy Days are a key part of that for Spiritual Israel today. They are times when He calls for His children to come together, rejoice with each other and with Him, and learn more about Him. That’s what we’ll be doing for the seven days of the Feast of Tabernacles and the Eight Day that follows, just as Jesus did when He kept this Feast (John 7).

Featured image by Claudine Chaussé

Song Recommendation: “Am Echad” (One People) by Ted Pearce