I’d planned to write more about the Hebrew word shamar (which we covered last week) today, but I heard an excellent sermon on the Parable of the Prodigal Son that made me want to write about this topic today. The main point was that we can learn from all three of the characters in this parable. At different points in our lives, we can be the prodigal son, the compassionate father, or the angry brother. The speaker made a point near the end of the message when talking about the angry brother that really stood out to me. He said, “We don’t pay the price of others’ sins.”

Now, at first, something in me grew hot and angry hearing this. I thought, “I’ve absolutely paid a price for other people’s sins when they’ve hurt me.” But then I realized that wasn’t the point of this statement. Yes, other people’s sins can affect us, sometimes very badly. However, the price of their sins that we’re talking about here refers to the price that God’s justice demands a sinner pay for violating His law. Ultimately, this price is death, or it would be without the sacrifice of Jesus (Rom. 6:23).

You see, while we can still suffer because of other people’s sins, we’re not the ones paying the price for forgiveness. We couldn’t; we also deserve a death penalty for our sins and we can’t offer ourselves in exchange for someone else’s soul even if we wanted to (Ezk. 18:20). This also means we don’t have the right to withhold forgiveness.

Forgiveness and Restoration

Forgiveness can be a tough subject for many of us. Many of us struggle with forgiveness even if we know we should do it, or we come up with reasons why we don’t need to forgive in particular cases. Trust me, I know it’s hard. It’s not like I’ve never been hurt by anyone and I’m saying “just forgive them” without knowing how hard that is. But even if you go through something traumatic and still have occasional panicked flashbacks, you need to forgive. Even if you ended up in counseling for 3 years trying to figure out how to process what happened, you need to forgive.

For if you forgive others their sins, your heavenly Father will also forgive you. But if you do not forgive others, your Father will not forgive you your sins.

Matthew 5:14-15, NET

We think of forgiveness as something God offers us freely, but in reality it’s conditional on something. If we want forgiveness, then we need to forgive others. There’s no wiggle room in here. There are, however, some things forgiveness doesn’t necessarily entail.

Forgiveness doesn’t always mean restoring relationships–sometimes it’s not safe or healthy to continue having any kind of relationship with the person who wronged you. This is especially true if they don’t repent. For example, Paul told the Corinthians to stop associating with someone who was flagrantly sinning without repentance (1 Cor. 5), then later told them to restore someone that we assume is the same man to their fellowship of believers after his repentance (2 Cor. 2:5-11; 7:8-12). The relationship wasn’t restored until the person repented and changed his conduct. Jesus also gave step-by-step instructions for attempting to reconcile with a fellow believer if they sin, but also said that if it doesn’t work you don’t have to keep trying (Matt. 18:15-17).

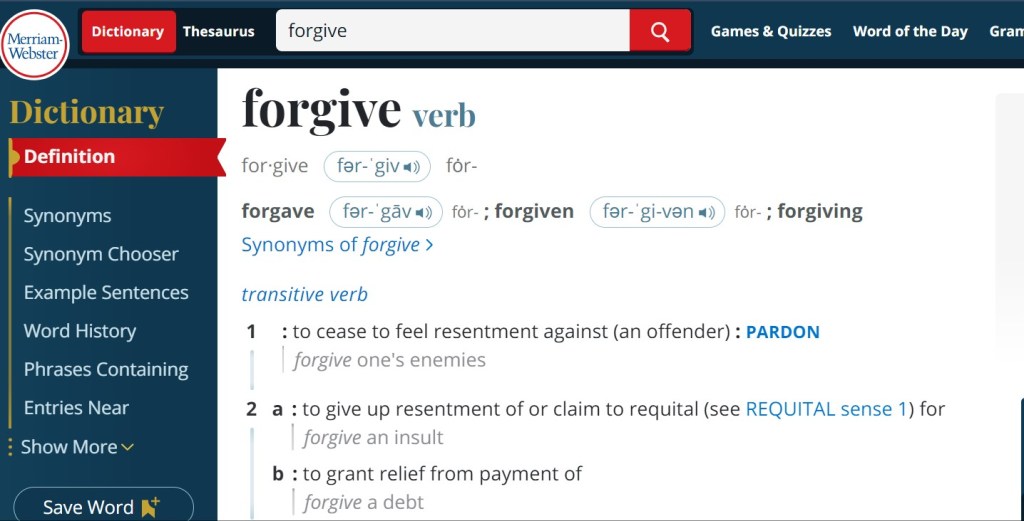

Reconciliation, peace, and restored relationships is the goal for Christians, but there’s also only so much we can do if the other person isn’t repenting, changing, or trying. We’re only responsible for our own actions and can’t control others (Rom. 12:9-21). One of the actions that we can take on our own without the other person doing anything is forgive. In the New Testament, sin is often framed as a debt (e.g. when we sin, we owe God something that we can’t pay back). This is reflected in one line from Jesus’s model prayer: “forgive us our debts, as we ourselves have forgiven our debtors.” If someone owes you something, you can cancel that debt. In other words, we can let go of bitterness, anger, resentment, and the sense that we’re owed something. Forgiveness is a necessary and healthy thing to do, whether or not the other person asks for it.

Why We Must Forgive

One of Jesus’s parables expands on why forgiveness is something He can and does command us to do (Matt. 18:21-35). In this parable, a king (who pictures God) forgives a servant who owes him a massive sum of money. His debt is 10,000 talents, which is equal to about what a typical person could earn in 164,384 years of work (1 talent=6,000 denarii, and 1 denarius=1 day of work; see NET footnote on Matt. 18:24). Incredibly, the king forgives the debt. Then, right after receiving forgiveness, the man goes out and shakes down a fellow slave who owed him just 100 denarii, or about 3 months’ wages. He refuses to forgive right after he’s been forgiven.

“When his fellow slaves saw what had happened, they were very upset and went and told their lord everything that had taken place. Then his lord called the first slave and said to him, ‘Evil slave! I forgave you all that debt because you begged me! Should you not have shown mercy to your fellow slave, just as I showed it to you?’ And in anger his lord turned him over to the prison guards to torture him until he repaid all he owed. So also my heavenly Father will do to you, if each of you does not forgive your brother from your heart.”

Matthew 18:31-35, NET

As people who’ve received God’s forgiveness, we’re obligated to forgive others. As in this parable, we should be able to recognize how ridiculous it is for someone forgiven an unfathomably large debt to then refuse to forgive others a paltry sum. No matter how much someone “owes” us (or seems to) for their sin, they owe God more. If He, who is owed so much, can choose to forgive and remove the death penalty for sin, how much more should we, who are owed comparatively little, choose to stop inflicting a penalty on people who’ve wronged us.

God’s instruction to forgive should be enough for us. But there’s also research to back-up the importance of forgiveness for our own wellbeing. According to surveys by the American Bible Society published in their ebook “State of the Bible USA 2024,” people who can forgive are much better off than those who can’t or won’t. The survey asked if the respondent agreed with the statement, “I am able to sincerely forgive whatever someone else has done to me, regardless of whether they ever ask for forgiveness or not.” Those who agreed also scored higher on Human Flourishing and Hope Agency (p. 54-55), demonstrated more pro-social behaviors (p. 73), and were significantly less lonely than unforgiving people (p. 166). Forgiveness is healthy for us, helps us move forward with hope, and improves relationships with other people. God tells us to do this for our own good.

Who Paid For Sin?

One of the things that Jesus didn’t touch on in the parable we just looked at is who paid the price for sins. When God forgives a sin, it’s not quite like the king who just waved a hand and made the debt go away. Someone still pays for that debt, and that someone is Jesus Christ.

For to this you were called, since Christ also suffered for you, leaving an example for you to follow in his steps. He committed no sin nor was deceit found in his mouth. When he was maligned, he did not answer back; when he suffered, he threatened no retaliation, but committed himself to God who judges justly. He himself bore our sins in his body on the tree, that we may cease from sinning and live for righteousness. By his wounds you were healed. For you were going astray like sheep but now you have turned back to the shepherd and guardian of your souls.

1 Peter 2:21-25, NET (bold italics mark quotations from Is. 53:5-6, 9; 53:4, 12)

Jesus took our sins on Himself. He “is the atoning sacrifice for our sins, and not only for our sins but also for the whole world” (1 John 2:2, NET). We often think of Jesus as “my savior,” but we might not always think of the implications of Him being the savior of the whole world. God didn’t just love me and send Jesus for me: He agape-loves everyone and sent Jesus to save the whole world (John 3:16).

I’m not preaching universal salvation here. God doesn’t apply salvation to everyone automatically–we have to accept the gift by repenting, believing, and entering a covenant relationship with God. But He does make salvation available to everyone because “he does not wish for any to perish but for all to come to repentance” (2 Pet. 3:9, NET). In other words, He’s already decided to forgive people if they ask Him for it.

Here, we come back to the point we started with: “We don’t pay the price of others’ sins.” Jesus did that when He offered His own life in exchange for the world. He canceled the debts of everyone who will come to God and take advantage of that offer. We don’t (and can’t) pay the final, cosmic price of others’ sins and we don’t have the right to withhold forgiveness from them. This is especially true if they repent and ask us to cancel their debt, but it’s also true that we need to let go and let God handle things even if the other person doesn’t repent or ask us for forgiveness.

Featured image by Chris Mainland from Lightstock

Song Recommendation: “That’s How You Forgive” by Shane & Shane