Several years ago, I did a study on Hebrew words for praise and discussed six different words translated “praise” in the KJV (yadah, zamar, todah, halel, tehillah, and barak). Last year, when I was studying song in connection to prophecy, I also started collecting scriptures related to singing praise. Finally, this spring, I collected those scriptures into a list of 30 to share with my ladies’ scripture-writing group at church.

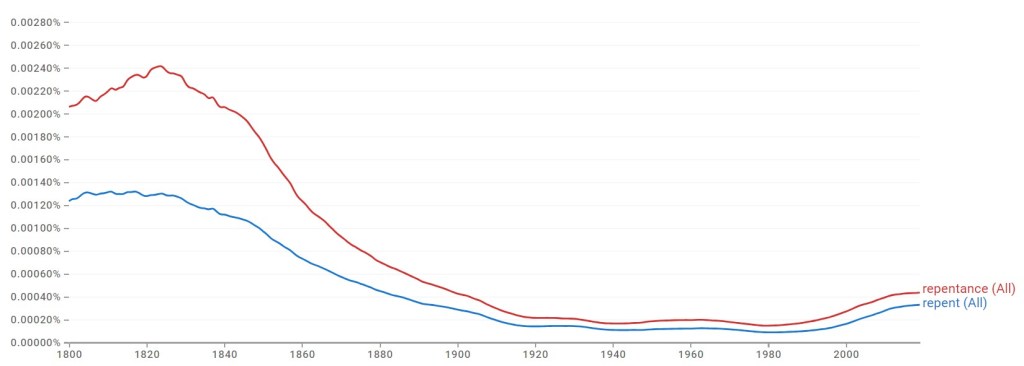

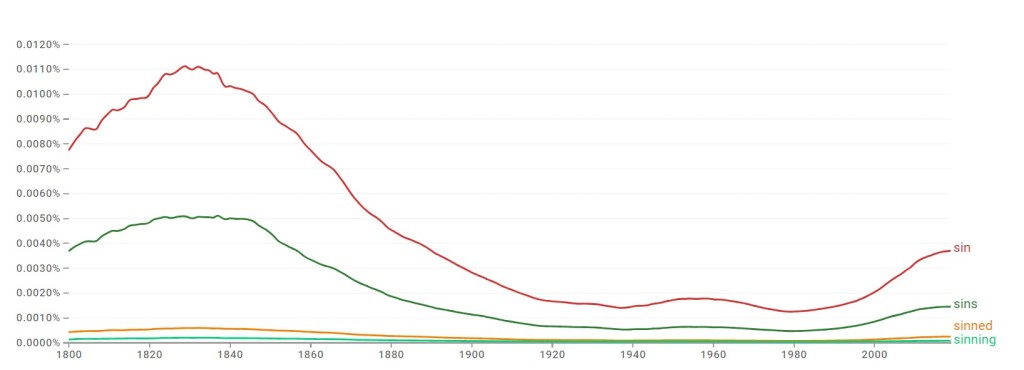

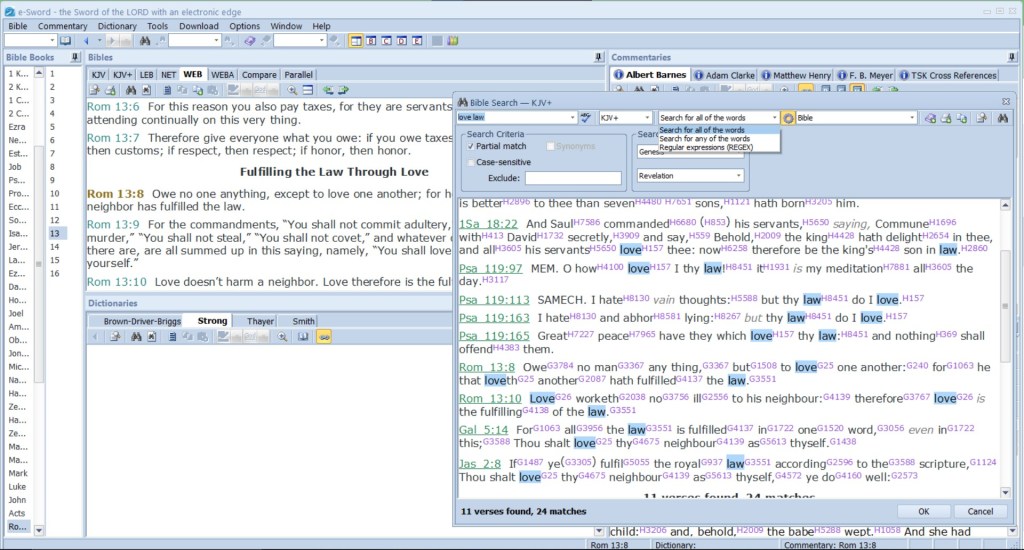

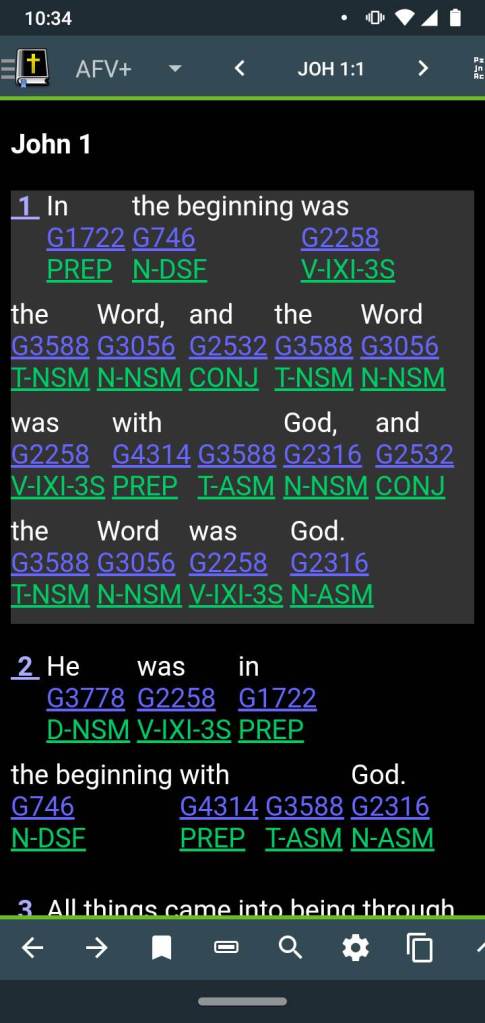

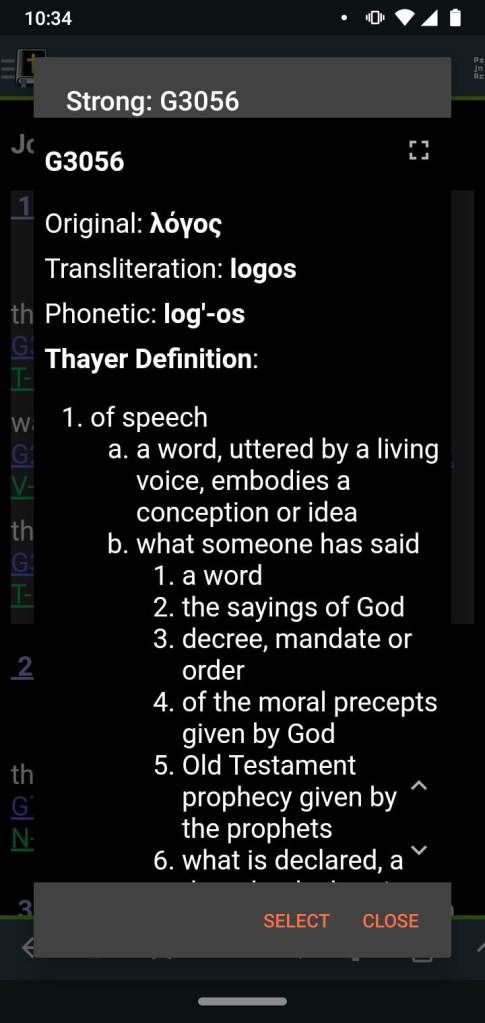

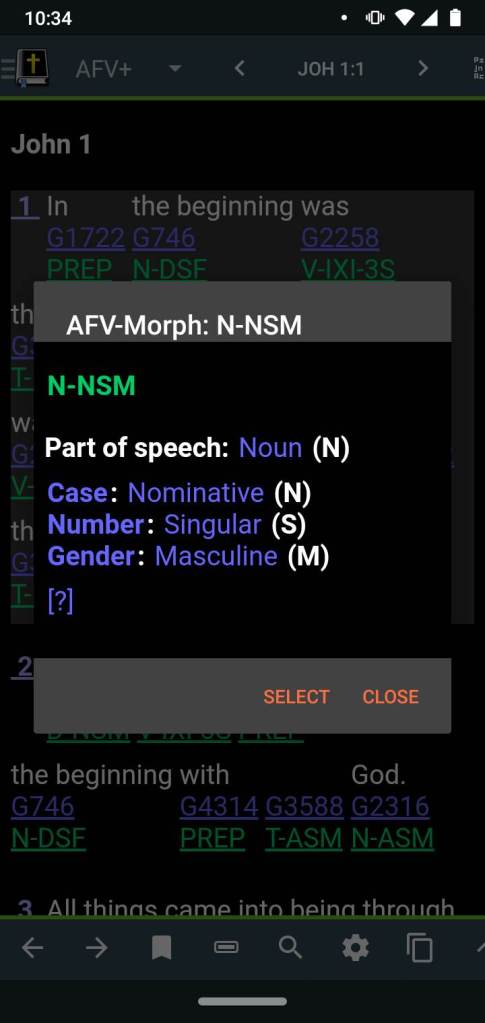

One of the things I worried about when I shared this list was that 22 out of 30 were from Psalms. Typically, I like to draw from all over the Bible but for this one, most of the on-topic verses were in Psalms (not surprising, considering what we’re studying). I worried it might start to seem monotonous to write out verses from psalms over and over each day that basically all read as “sing praise to God.” But there’s a lot more variation in those verses than it seems when writing them in English. As I wrote these scriptures throughout February, I also wrote down the Hebrew words translated “sing,” “praise,” and occasionally “thanks.” It’s just two or three words in English, but in Hebrew there’s zamar, zamiyr, zimral, shur, shiyr, yadah, halel, tehillah, tephillah, ranan, renanah, todah, anah, and shaback.

I find the wide variety of Hebrew words that surround the concept of praise and song fascinating, particularly since Hebrew has a far smaller pool of words than English. There are “about eight thousand words” in the Hebrew language, in contrast to “one hundred thousand or more in our language” (Reading the Bible with Rabbi Jesus: How a Jewish Perspective Can Transform Your Understanding, Lois Tverberg, p. 61). Given that vast difference between the two languages, you’d expect that English would be the one with tons of words that are synonymous with praise (it does to a certain extent, but you don’t often see words like commend, compliment, extol, applaud, etc. used in English scripture). Praise must be extremely important to the Hebrew people for them to devote so many of their words to this concept.

To help illustrate this point, let’s look at a concept that the English language places a high value on: the legal system and government. There are a ton of different words for government, branches of government, and the systems of government. But Hebrew doesn’t have words for separating the legislative, executive, and judicial functions of government. They combine everything into one word shapat/mishpat, which Bible translators often render as “justice.” It’s a reflection of a culture where all that authority is centered in God and the king as His representative on earth. In contrast, English reflects a culture where government functions are divided up among different people and conceptualized differently.

It’s similar with praise. In English, we think of praise and worship together and mostly associate it with singing Christian music. We might also include praise in the sense of thanking or acknowledging God for good things that He has done. But praise in Old Testament Hebrew culture is much more varied and vital a concept, and that’s reflected in the number of words the language uses to denote specific types of praise.

Halal–glorifying God with praise

Even if you know nothing about Hebrew, you probably know this word because of our English “hallelujah” (literally, praise Yah[weh]). The root word halal (H1984) appears 165 times in the Old Testament. It can mean to shine, boast, or even “act like a madman” (Brown, Driver, Briggs [BDB]) but most often it means praise. Basically, it “connotes being sincerely and deeply thankful for and/or satisfied in lauding” something or someone (Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament [TWOT], entry 500). One noun form, tehilla (H8416), also appears fairly often in the Old Testament (57 times). It “represents the results of halal as well as divine acts which merit that activity” (TWOT 500c). Tehilla can also be linked specifically to a “song or hymn of praise” (BDB, H8416).

Praise (halal) Yah!

Praise Yahweh from the heavens!

Praise him in the heights! …let them praise (halal) Yahweh’s name,

Psalm 148:1, 13-14, WEB

for his name alone is exalted.

His glory is above the earth and the heavens.

He has lifted up the horn of his people,

the praise (tehilla) of all his saints,

even of the children of Israel, a people near to him.

Praise (halal) Yah!

Typically in the Bible, halal is used to praise and glorify God. It’s linked with joy, speaking, singing, dancing, and intelligent expression. Interestingly, “most of these occurrences are plural … [showing] that the praise of Jehovah was especially, though by no means uniquely … congregational” (TWOT 500). We can and should praise when we’re alone, but praise is something that’s expected when God’s people gather together. That’s why so many churches sing songs that glorify God as part of their formal services.

Praise (halal) Yah!

Psalm 150, WEB

Praise God in his sanctuary!

Praise him in his heavens for his acts of power!

Praise him for his mighty acts!

Praise him according to his excellent greatness!

Praise him with the sounding of the trumpet!

Praise him with harp and lyre!

Praise him with tambourine and dancing!

Praise him with stringed instruments and flute!

Praise him with loud cymbals!

Praise him with resounding cymbals!

Let everything that has breath praise Yah!

Praise Yah!

Song Recommendation: “Hallelu Et Adonai” (Praise the Lord) by Ted Pearce

Yadah–confessing God is worthy of praise

Another very common Hebrew word for praise is yadah (H3034). It appears 114 times in the Old Testament. This one is often translated “give thanks,” though it’s also translated “praise” or “confess.” The “thanks” translation can be misleading, though, because there really isn’t an Old Testament equivalent to our concept of “to thank” (TWOT 847). In the Bible, thanks “is a way of praising” God rather than something we do, such as say “thank you” to other people. “Confession” is probably the best English equivalent to yadah (TWOT).

Oh, send out your light and your truth.

Psalm 43:3-5, WEB

Let them lead me.

Let them bring me to your holy hill,

to your tents.

Then I will go to the altar of God,

to God, my exceeding joy.

I will praise (yadah) you on the harp, God, my God.

Why are you in despair, my soul?

Why are you disturbed within me?

Hope in God!

For I shall still praise (yadah) him:

my Savior, my helper, and my God.

In the sense of praise or thanks, yadah has to do with acknowledgement, “‘recognition’ and ‘declaration’ of a fact” (TWOT 847). The word can be used in a good or bad sense: for example, confessing sin or acknowledging God’s goodness. The noun todah (H8426) has basically the same meaning, and is often associated with offerings (e.g. “thank offering” or “praise offering”) (TWOT 847b).

Barak–blessing or praising

Barak (H1288) is used 285 times in the Old Testament (or 415 if you include all the root’s derivatives), and it’s usually translated “bless.” The basic meaning may be “to kneel” (TWOT 285). It’s often used of God blessing people, but when it’s used of people blessing God it can be seen as a type of praise.

Praise (barak) our God, you peoples!

Psalm 66:8, WEB

Make the sound of his praise (tehilla) heard,

When we looked at yadah earlier, one of the things I didn’t mention is that the root word is likely related to throwing or casting something with the hands (BDB). It makes me think of Paul’s desire that “the men in every place pray, lifting up holy hands” (1 Tim. 2:8, WEB). Lifting hands when praising God can be controversial (some churches discourage or even forbid it, while in others it’s normal), but it’s definitely Biblical. In psalms, lifting hands is linked with praise.

So I will bless (barak) you while I live.

Psalm 63:4, WEB

I will lift up my hands in your name.

Lift up your hands in the sanctuary.

Psalm 134:2, WEB

Praise (barak) Yahweh!

With the link between barak and kneeling as well as its use with lifting hands in praise, I think it’s safe to say we could classify this as one of the physical types of praise. In many cases, we’ll see that praise involves our voices and bodies as well as our thoughts. You can praise God in your mind, but you’re also supposed to praise Him with your voice and with your body (e.g. kneeling, lifting hands, dancing).

Song Recommendation: “Blessed is the Lord” (Baruch atah Adonai) by Paul Wilbur

Zamar–singing or playing praise music

The word zamar (H2167) basically means to sing or to play an instrument. But it’s used so much in the Old Testament in relation to praise that it’s typically translated “sing praise.” It might not always mean singing, though, as it’s also linked with playing lyre, harp, and tambourine (TWOT 558). This may imply that praise music typically has lyrics, but can also be instrumental. This word appears 45 times in the Old Testament.

I will give thanks (yadah) to Yahweh according to his righteousness,

Psalm 7:17, WEB

and will sing praise (zamar) to the name of Yahweh Most High.

Make a joyful shout to God, all the earth!

Psalm 66:1-2, WEB

Sing (zamar) to the glory of his name!

Offer glory and praise (tehilla)!

Words translated “psalm” or melody, like zimrah and mizmor, are derivatives of zamar. Over and over in scripture, you’ll see praise linked with music and specifically song. Whether we have perfect pitch or we’re just making a joyful noise, we shouldn’t be shy to express our adoration for God through music or even shouts of joy.

Make a joyful noise to Yahweh, all the earth!

Psalm 98:4, WEB

Burst out and sing for joy, yes, sing praises (zamar)!

Sing praises (zamar) to Yahweh with the harp,

with the harp and the voice of melody (zimrah).

With trumpets and sound of the ram’s horn,

make a joyful noise before the King, Yahweh.

Ranan–crying out praises

The basic meaning of ranan (H7442) is “to cry out, shout for joy, give a ringing cry” (BDB). Typically, it’s used of crying out to God for some reason, and in psalms it’s often paired with joy and singing. The word might even mean to sing out joyful praises, depending on the context: “The jubilation which is the main thrust of the root … could equally well be expressed in shouting or song” (TWOT 2179). One of the noun forms, renanah (H733) is “a ringing cry, shout (for joy)” and can be translated “singing” (BDB).

Shout for joy to Yahweh, all you lands!

Psalm 100, WEB

Serve Yahweh with gladness.

Come before his presence with singing (renanah).

Know that Yahweh, he is God.

It is he who has made us, and we are his.

We are his people, and the sheep of his pasture.

Enter into his gates with thanksgiving (todah),

and into his courts with praise (tehilla).

Give thanks (yadah) to him, and bless (barak) his name.

For Yahweh is good.

His loving kindness endures forever,

his faithfulness to all generations.

Shir–songs, often of praise

The words for “sing” and “song” are not confined to religious music, but they are so often linked with praise that it’s worth mentioning them in this study. The Hebrew word shir or shiyrah (H7892) is often used in the psalms, both to describe what is being written (e.g. “a song of ascents” for Ps. 120-134) and as part of the text of the psalm (e.g. “with my song I will thank him” [Ps. 28:7, WEB]).

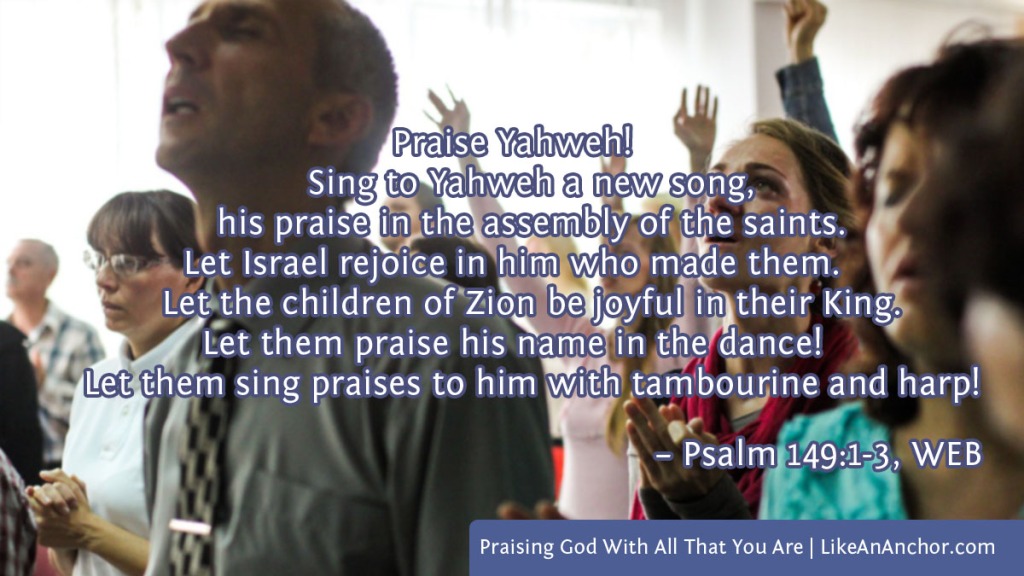

Praise (halal) Yahweh! Sing (shir) to Yahweh a new song, his praise (tehilla) in the assembly of the saints.

Psalm 149:1, WEB

Shir is typically used for hymns and psalms of lament. Both can be linked to praise. Many songs of lament “evolve into songs of praise in anticipation of God’s deliverance.” Hymns involve singing to God “in response to something already experienced” (TWOT 23781). Often, this type of song involves praising who or what God is or confessing/thanking Him for things that He has done. As I mentioned earlier, the topic “sing praise” is what prompted this blog post. You can download my free 30-day scripture writing plan and keep studying this topic on your own by clicking here.

Song Recommendation: “Gadol Elohai/How Great Is Our God” by Joshua Aaron

Gadal–praising God’s greatness

The TWOT lists gadal (H1431) or gadol (H1419) in the sense of “to magnify” as one of the synonyms for halel (TWOT 500). You’re not likely to find it if you search for Hebrew words translated “praise” in English Bibles (it’s most often translated “great”), but the usage is linked to praise.

Great (gadol) is Yahweh, and greatly to be praised (halal),

Psalm 48:1, WEB

in the city of our God, in his holy mountain.

I will praise (halal) the name of God with a song (shir),

Psalm 69:30, WEB

and will magnify (gadal) him with thanksgiving (todah).

The root verb gadal means to “grow up, become great or important … praise, (magnify), do great things” (TWOT 315). In certain verb stems, it can mean “to magnify” or “consider great.” It’s often used to speak of God’s greatness or to talk about how God magnifies Himself. The adjective gadol has a similar range of meanings (TWOT 315d). Together, the two words appear a total of 643 times in the Old Testament.

Rum–lifting God high for praise

The TWOT lists rum (H7311) in the sense of “to exalt” as one of the synonyms for halel (TWOT 500). The root has three basic meanings: “literal height,” “height as symbolic of positive notions such as glory and exaltation,” and “height as symbolic of negative notions such as arrogance and pride” (TWOT 2133). We can “exalt God in praising” Him, or lift His name high. One specific derivative, romam (H7319), means “high praises” (TWOT 2133f).

May the high praises (romam) of God be in their mouths,

Psalm 149:6, WEB

and a two-edged sword in their hand

Shabach–praise His mighty deeds

The verb shabach (H7623) only appears 11 times in the Old Testament. It means to praise, laud, or commend (BDB). Typically, it’s “used to praise God for his mighty acts and deeds” (TWOT 2313).

Because your loving kindness is better than life,

Psalm 63:3-5, WEB

my lips shall praise (shabach) you.

So I will bless (barak) you while I live.

I will lift up my hands in your name.

My soul shall be satisfied as with the richest food.

My mouth shall praise (halal) you with joyful lips,

Psalm 117, WEB

Praise (halal) Yahweh, all you nations!

Extol (shabach) him, all you peoples!

For his loving kindness is great toward us.

Yahweh’s faithfulness endures forever.

Praise (halal) Yah!

Why Study Praise Words?

So why did we spend all this time looking at nine Hebrew words (more if you include derivatives from the root words) that all translate into English so similarly?

In an English Bible, “praise” appears hundreds of times, depending no the translation (254 in WEB, 259 in KJV, 328 in NET, 363 in NIV). It’s a vital concept in scripture, and something that we need to understand how to do if we’re to relate properly to God. One of our purposes for being here as Christians is to praise Him. Our lives should praise God, as well as our lips (Phil. 1:9-11; Heb. 13:14-15).

In Christ we too have been claimed as God’s own possession, since we were predestined according to the purpose of him who accomplishes all things according to the counsel of his will so that we, who were the first to set our hope on Christ, would be to the praise of his glory.

Ephesians 1:11-12, NET

If we just looked at the English word for praise, we’d think the definition was limited to “express warm approval or admiration of” and “express one’s respect and gratitude toward (a deity), especially in song” (definitions from Google and Oxford Languages). Studying the variety of Hebrew words related to praise gives us a much broader appreciation of praise. It’s more than just approval, admiration, respect, and gratitude. It’s a whole-life, whole-body, whole-heart expression of God’s glory, our thankfulness, and much more.

Featured image by Pearl from Lightstock