Sometimes, reading familiar verses in a new translation can give you just enough of a perspective shift that they hit you a different way than before. I’ve been using the New English Translation for a few years now, but there are still some books I haven’t spent as much time in and the wording really makes me sit up and take notice. That happened this week when I was reading Titus 3:8 for my ladies’ group’s 30-day scripture writing program this month.

This saying is trustworthy, and I want you to insist on such truths, so that those who have placed their faith in God may be intent on engaging in good works. These things are good and beneficial for all people.

Titus 3:8, NET

The phrase “I want you to insist on such truths” was translated “concerning these things I desire that you affirm confidently” in the WEB, which is more literal. However, I like the way the NET calls attention to Paul’s emphasis on affirming truthful, trustworthy things. It made me want to meditate and study more deeply on Paul’s goal in writing this letter.

To Further The Faith

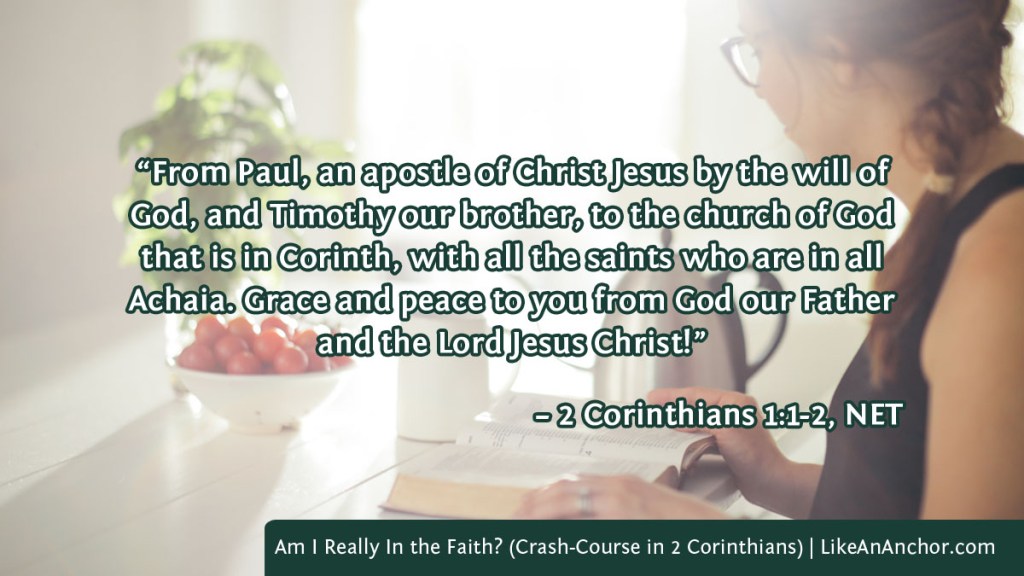

In a letter to the Corinthians, Paul called Titus a “brother,” partner, and “fellow worker,” and described his presence as a joy and comfort (2 Cor. 2:13; 7:6, 13-14; 8:6, 16, 23; 12:18). We also know from Galatians that Titus was a Greek, which caused some contention among Jewish believers who wanted to insist non-Jewish male converts be circumcized (Gal. 2:1-10). We don’t know much else about him from the Bible, but we know he traveled with Paul on ministerial work and that Paul left him in Crete “to set in order the remaining matters and to appoint elders in every town” ( Titus 1:5, NET). That’s where Titus was when Paul wrote him the letter that we have in our New Testaments today.

From Paul, a slave of God and apostle of Jesus Christ, to further the faith of God’s chosen ones and the knowledge of the truth that is in keeping with godliness, in hope of eternal life, which God, who does not lie, promised before time began. But now in his own time he has made his message evident through the preaching I was entrusted with according to the command of God our Savior. To Titus, my genuine son in a common faith. Grace and peace from God the Father and Christ Jesus our Savior!

Titus 1:1-4, NET

Look at how Paul describes his role in the opening salutation of this letter. He is a slave or bondservant (i.e. one who sells himself in service to another) belonging to God; in other words, he doesn’t see himself as free to leave but his service is voluntary. And the purpose of being “a slave of God and apostle of Jesus” is “to further the faith of God’s chosen ones and the knowledge of the truth that is in keeping with godliness.” We’ve been studying faith a lot on this blog recently, particularly in connection with covenant faithfulness. We can think of faith in the first-century Biblical context as “active loyalty, trust, hope, knowledge, and persuasion … within the new covenant brought about through Christ’s Atonement” (Brent Schmidt, Relational Faith, p. 11). That’s what Paul wanted to “further” among God’s chosen ones as he shared knowledge of Truth “in hope of eternal life.”

Faith, truth, and hope are also something Paul wants others to share. As I mentioned, he left Titus in Crete to appoint elders, and the next thing Paul focuses on in his letter is qualifications for those elders. Some of those qualifications have to do with the elder’s family, others with his character, and finally with his commitment to teaching God’s word correctly (Titus 1:5-9).

He must hold firmly to the faithful message as it has been taught, so that he will be able to give exhortation in such healthy teaching and correct those who speak against it.

For there are many rebellious people, idle talkers, and deceivers, especially those with Jewish connections, who must be silenced because they mislead whole families by teaching for dishonest gain what ought not to be taught.

Titus 1:9-11, NET

Here’s where the NET translators made what I think is a misstep. They translated “those of the circumcision” as “those with Jewish connections,” which implies that anyone with Jewish links was an issue when in reality Paul was addressing a specific faction that taught circumcision was necessary for salvation and wanted to enforce extra-Biblical Jewish teachings on top of God’s laws.

For this reason rebuke them sharply that they may be healthy in the faith and not pay attention to Jewish myths and commands of people who reject the truth. All is pure to those who are pure. But to those who are corrupt and unbelieving, nothing is pure, but both their minds and consciences are corrupted. They profess to know God but with their deeds they deny him, since they are detestable, disobedient, and unfit for any good deed. But as for you, communicate the behavior that goes with sound teaching.

Titus 1:13-2:1, NET

One of the responsibilities of ministers like Paul, Titus, and the elders Titus was entrusted to pick out is to help other believers stay healthy in their faith. Here, Paul indicates that we can stay healthy in the faith by holding fast to truth (rather than rejecting it), acknowledging God by doing good deeds, and making sure our behavior aligns with sound teaching.

To Behave As God Intends

There’s a big focus here in Paul’s letter to Titus on good behavior and works. Paul instructs Titus to “communicate the behavior that goes with sound teaching” (NET) or “say the things which fit sound doctrine” (Titus 2:1, WEB). He then goes on to give instructions specifically for older men and women, for younger women, for young men like Titus, and for servants (Titus 2:1-10). Then, Paul shares instructions that apply to all groups.

For the grace of God has appeared, bringing salvation to all people. It trains us to reject godless ways and worldly desires and to live self-controlled, upright, and godly lives in the present age, as we wait for the happy fulfillment of our hope in the glorious appearing of our great God and Savior, Jesus Christ. He gave himself for us to set us free from every kind of lawlessness and to purify for himself a people who are truly his, who are eager to do good. So communicate these things with the sort of exhortation or rebuke that carries full authority. Don’t let anyone look down on you.

Titus 2:11-15, NET

Here’s another spot where the phrasing in this translation really grabs my attention. It is “the grace of God” that “trains us to reject godless ways ” and to live in a way that honors God. This really highlights that grace is a gift that carries covenant obligations rather than some sort of carte blanche to live however we like. Jesus died to “set us free from every kind of lawlessness” and turn us into a people “who are eager to do good works” (NET footnote on 2:15 and other, more literal, translations add “works”).

Remind them to be subject to rulers and authorities, to be obedient, to be ready for every good work. …

This saying is trustworthy, and I want you to insist on such truths, so that those who have placed their faith in God may be intent on engaging in good works. These things are good and beneficial for all people. …

Here is another way that our people can learn to engage in good works to meet pressing needs and so not be unfruitful.

Titus 3:1, 8, 14, NET

It might seem surprising how much Paul focuses on works in this letter since he’s so often cited as the one who talks about dying to the law and not being saved by works. Reading his letter to Titus really hammers home how often Paul is misinterpreted. Here, as in all his letters, he teaches that New Covenant Christians are supposed to keep the spirit of the law; this actually carries a higher expectation than simply keeping the letter. And though we’re certainly not saved by our own works, we are saved with the expectation that we will then do good works.

To Maintain a Godly Perspective

The last of the three main themes that I see Paul focusing on in Titus has to do with how to view other people and your own calling. Remember, he has already reminded Titus that “the grace of God has appeared, bringing salvation to all people” (Tit. 2:11, NET). All, not just some. That doesn’t mean Paul thinks every human being is automatically saved as a result of Jesus’s death, but it does mean that He didn’t die for only one group of people. God loves the whole world and offers salvation to everyone. We must never forget that.

Remind them to be subject to rulers and authorities, to be obedient, to be ready for every good work. They must not slander anyone, but be peaceable, gentle, showing complete courtesy to all people. For we too were once foolish, disobedient, misled, enslaved to various passions and desires, spending our lives in evil and envy, hateful and hating one another. But “when the kindness of God our Savior and his love for mankind appeared, he saved us not by works of righteousness that we have done but on the basis of his mercy, through the washing of the new birth and the renewing of the Holy Spirit, whom he poured out on us in full measure through Jesus Christ our Savior. And so, since we have been justified by his grace, we become heirs with the confident expectation of eternal life.”

Titus 3:1-7, NET

The same mercy that saved us is available to even the most irritating people we meet. And as people who were just like that before our relationship with God (and could be just as “foolish, disobedient, misled, enslaved, … evil and … hateful” again if we reject God’s guidance), we should have compassion toward those who have not (yet) accepted the gift of God’s powerful grace. It is “this saying” which is “trustworthy” and that Paul calls Titus to insist upon so that Christians might focus intently on “engaging in good works.”

This saying is trustworthy, and I want you to insist on such truths, so that those who have placed their faith in God may be intent on engaging in good works. These things are good and beneficial for all people. But avoid foolish controversies, genealogies, quarrels, and fights about the law, because they are useless and empty. Reject a divisive person after one or two warnings. You know that such a person is twisted by sin and is conscious of it himself.

Titus 3:8-11, NET

As I mentioned in my last two posts (“Do Not Forsake” and “The Necessity of Godly Conflict Resolution and Forgiveness“), there are times when we need to reject fellowship with someone who is sinful and toxic. One of the few times we’re told to do this is when someone is purposefully, unrepentantly causing divisions and quarrels. Spreading discord is one of the seven abominable things that God hates (Prov. 6:16-19). This means that we also need to vigilantly watch ourselves and make sure we avoid such useless, empty fights.

Paul’s letter to Titus is encouraging and instructive. He wants Titus and others who, like him, are entrusted with teaching and leading roles, to help further other believer’s faith, to behave as God intends, and to maintain a Godly perspective on themselves, their fellow believers, and those outside the faith. Those who aren’t elders or in other leadership roles can also learn from this, because the things Paul focuses on teaching and encouraging are the things we’re supposed to work on as well. We need to commit to growing in the faith, to making sure our deeds align with God’s ways, and to having a humble, godly perspective.

Featured image by Creative Clicks Photography from Lightstock