When I was writing last week’s post about inheriting covenants, I found myself writing a lot about Galatians. At one point while drafting, more than half that post was just about chapters 2 and 3. I decided to copy all that I’d written into a new post, condense the Galatians section, and focus entirely on Galatians this week.

I don’t usually spend much time in Galatians, at least not writing about it here on the blog (though I did previously write another “crash course” post on it 4 years ago). I’ve more than made up for that in today’s post, though, which is quite long (apologies for the 4,000 word article).

My reason for avoiding Galatians is it’s very easy to misinterpret, and I usually don’t want to take the time to contextualize verses from it and/or I’m not quite sure how to explicate them correctly. It’s easier to quote from other books, at least when we’re talking about a subject like covenants or a Christian’s relationship to God’s law. The “I am crucified with Christ,” fruit of the spirit, and “sowing and reaping” sections are the easiest to understand, so that’s where I (and most people I know of) spend most of their time if they go to Galatians. Today, though, we’ll do our best to study the whole thing.

Context and Background

Galatians is one of the letters that Paul likely wrote with co-authors. He began the letter, “Paul … and all the brothers with me, to the churches of Galatia” (Gal. 1:1-2. NET). Though Paul wrote this letter with his own hands (Gal. 6:11), it seems that he collaborated, at least to some extent, with other believers. That would make sense considering the subject matter; Paul’s main focus is on correcting errors in the Galatian’s theology. Bringing in others to consult on and probably proofread the letter makes it less about Paul and more about the truth held by trusted, established followers of Jesus.

Paul also takes great care to outline his qualifications as an authority on the subject of the true gospel. He can write to correct distorted gospels because he is “an apostle (not from men, nor by human agency, but by Jesus Christ and God the Father who raised him from the dead)” (Gal. 1:1, NET). He also reminds his readers “that the gospel I preached is not of human origin. For I did not receive it or learn it from any human source; instead I received it by a revelation of Jesus Christ” (Gal. 1:11-12, NET). Right off the bat, Paul wants to be very clear that the gospel Galatian believers originally received came straight from Jesus and was verified by the apostles who’d been personally taught by Jesus (Gal. 1:13-2:10). That understanding helps contextualize Paul’s shock that he would even need to write this letter.

I am astonished that you are so quickly deserting the one who called you by the grace of Christ and are following a different gospel—not that there really is another gospel, but there are some who are disturbing you and wanting to distort the gospel of Christ. But even if we (or an angel from heaven) should preach a gospel contrary to the one we preached to you, let him be condemned to hell! As we have said before, and now I say again, if any one is preaching to you a gospel contrary to what you received, let him be condemned to hell! Am I now trying to gain the approval of people, or of God? Or am I trying to please people? If I were still trying to please people, I would not be a slave of Christ!

Galatians 1:6-10, NET

We’re not sure exactly when Galatians was written, but it was at some point after Paul had preached the gospel to churches in this region. Like most of his letters, he’s writing to a group that he already has a relationship with and addresses something specific that’s going on in the church.

One exception to this pattern is the letter to Rome; Paul hadn’t been there before, and Romans is an introduction of sorts (Rom. 1:8-15; 15:22-24). That makes Romans very helpful in understanding Galatians; we can assume that the foundational theology Paul outlines in Romans is pretty much what he would have preached to the Galatians. Since the gospel he preached came straight from Jesus, it wouldn’t have been changing from church-to-church or over the course of Paul’s ministry.

Likewise, we can use the gospels as guides to interpret Galatians (as well as Paul’s other writings). As a faithful apostle, Paul would not have contradicted any of Jesus’s teachings. If there’s ever a case where we’re not sure what Paul meant (and he can be tricky to interpret, as even Peter points out [2 Pet. 3:15-16]), we need to compare what he’s saying to Jesus’s teachings. Whatever interpretation we go with must agree with Jesus. We won’t talk about the General Epistles much in today’s post, but those are also helpful pre-reqs for understanding Paul.

Paul Setting The Stage

Paul does not outline the specifics of the heresy in Galatia. He assumes his readers already know what’s going on. Those of us divorced from this context have to read closely and draw conclusions from the letter and what Acts tells us about similar questions. It appears that the Galatian believers had been deceived by someone who came in and told them they needed to keep the whole Jewish law in order to be saved. The Galatians were worried that male believers needed to be circumcised, that they all had to keep the whole Old Covenant law, and that they additionally had to keep Jewish additions to God’s law.

A large section of the letter’s introduction is devoted to Paul explaining his ministry and pointing out that the true Christian apostles never compelled new Gentile converts to be circumcised (see Acts. 11 and 15). Male circumcision was a key part of the Abrahamic Covenant, which continued for ancient Israel into the Sinai Covenant and up to the time of Jesus. Paul addressed the question of whether new converts to following Jesus the Messiah should be circumcised in several letters. Taken together, his basic explanation was that New Covenant circumcision happens in the heart rather than as a physical sign (which aligns perfectly with God’s Old Testament intention as well [Deut. 10:16; 30:6; Jer. 4:4; 9:26; Rom. 2:29; Phil. 3:3; Col. 2:11-12]).

But when Cephas [Peter] came to Antioch, I opposed him to his face, because he had clearly done wrong. Until certain people came from James, he had been eating with the Gentiles. But when they arrived, he stopped doing this and separated himself because he was afraid of those who were pro-circumcision. …

We are Jews by birth and not Gentile sinners, yet we know that no one is justified by the works of the law but by the faithfulness of Jesus Christ. And we have come to believe in Christ Jesus, so that we may be justified by the faithfulness of Christ and not by the works of the law, because by the works of the law no one will be justified. But if while seeking to be justified in Christ we ourselves have also been found to be sinners, is Christ then one who encourages sin? Absolutely not! But if I build up again those things I once destroyed, I demonstrate that I am one who breaks God’s law. For through the law I died to the law so that I may live to God.

I have been crucified with Christ, and it is no longer I who live, but Christ lives in me. So the life I now live in the body, I live because of the faithfulness of the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me. I do not set aside God’s grace, because if righteousness could come through the law, then Christ died for nothing!

Galatians 2:11-12, 15-21, NET

In other words, the Old Covenant ended with Jesus’s death and a New Covenant took its place. We certainly don’t live lawlessly now, but we live with the knowledge that we can’t make ourselves righteous. Jesus’s faithfulness brings us righteousness and justification. The moment we think we’re saved by our own efforts rather than Christ’s sacrifice, we’ve set aside God’s grace. That doesn’t mean we break God’s law now; Christ in us does not encourage sin nor did He do away with God’s law (Matt. 5:17-20; Rom. 3:28-31). But He also didn’t redeem us and give us the Spirit so that we could then try to save ourselves by our own efforts.

You foolish Galatians! Who has cast a spell on you? Before your eyes Jesus Christ was vividly portrayed as crucified! The only thing I want to learn from you is this: Did you receive the Spirit by doing the works of the law or by believing what you heard? Are you so foolish? Although you began with the Spirit, are you now trying to finish by human effort? Have you suffered so many things for nothing?—if indeed it was for nothing. Does God then give you the Spirit and work miracles among you by your doing the works of the law or by your believing what you heard?

Galatians 3:1-5, NET

These questions prime the Galatians for the next parts of Paul’s argument. He defends the gospel he preached previously, then asks questions to wake them up to ways they’d distorted the gospel. From the way Paul speaks, I assume the Galatians made one of two errors very common to people trying to follow Jesus.

Sometimes, we err by becoming too permissive and thinking that God’s grace means we have no responsibilities and that law doesn’t exist anymore (Paul addressed this with the Corinthians, who prided themselves on allowing sin in the congregation). Other times, we’re more like the Galatians and error by thinking that if we do every command written in the Bible just right and maybe add some Jewish tradition on top of that, then we’ll make ourselves good enough to deserve salvation. Neither is correct.

Faith Like Abraham

Rather than present again the nuanced rhetorical argument of Romans, where Paul explains that the New Covenant replaces the Old Covenant entirely and elevates the Law of God to a higher, spiritual, internalized level, in Galatians Paul goes back even farther to the covenant God made with Abraham. For this letter, he needs to show that the Galatians are not saved by doing the works commanded in the law and counter the claim that new believers should be circumcised. To do that, he argues that New Covenant believers follow the same pattern that Abraham did even though they’re not doing the physical sign of that covenant.

Just as Abraham believed God, and it was credited to him as righteousness, so then, understand that those who believe are the sons of Abraham. And the scripture, foreseeing that God would justify the Gentiles by faith, proclaimed the gospel to Abraham ahead of time, saying, “All the nations will be blessed in you.” So then those who believe are blessed along with Abraham the believer.

Galatians 3:6-9, NET (bolt italics mark quotes from the Old Testament)

Here, Paul quotes from the record in Genesis of God cutting a covenant with Abraham (Gen. 15). This covenant is one of inheritance and blessing. We learn more about this in Genesis 17 and 18, which Paul also quotes. Back in Genesis, God said He would bless Abraham and that “I have chosen him so that he may command his children and his household after him to keep the way of the Lord by doing what is right and just. Then the Lord will give to Abraham what he promised him” (Gen. 18:19, NET). Notice that God’s covenant with Abraham included following the Lord’s way and doing what is right. But, as Paul emphasized, the promises come to Abraham and his descendants because God is faithful, not because they kept the Law that God later shared as part of the Sinai Covenant or because they observed Jewish traditions added later.

For all who rely on doing the works of the law are under a curse, because it is written, “Cursed is everyone who does not keep on doing everything written in the book of the law.” Now it is clear no one is justified before God by the law, because the righteous one will live by faith. But the law is not based on faith, but the one who does the works of the law will live by them. Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us (because it is written, “Cursed is everyone who hangs on a tree”) in order that in Christ Jesus the blessing of Abraham would come to the Gentiles, so that we could receive the promise of the Spirit by faith.

Galatians 3:10-14, NET (bolt italics mark quotes from the Old Testament)

God does want people to follow His law (it defines sin, and since sin is not consistent with God’s character it damages relationships between us and Him). But God also knows that all people sin and we can’t keep His law perfectly. It is very, very good for us that He upholds His parts of covenants even when people aren’t faithful, because one of those covenant promises was that God would send Jesus as the Messiah. That’s how we inherit the Abrahamic Covenant promises: through Jesus Christ.

Brothers and sisters, I offer an example from everyday life: When a covenant has been ratified, even though it is only a human contract, no one can set it aside or add anything to it. Now the promises were spoken to Abraham and to his descendant. Scripture does not say, “and to the descendants,” referring to many, but “and to your descendant,” referring to one, who is Christ. What I am saying is this: The law that came 430 years later does not cancel a covenant previously ratified by God, so as to invalidate the promise. For if the inheritance is based on the law, it is no longer based on the promise, but God graciously gave it to Abraham through the promise.

Galatians 3:15-18, NET (bolt italics mark quotes from the Old Testament)

A few verses later, Paul says that the Law was “added because of transgressions, until the arrival of the descendant to whom the promise had been made” (Gal. 3:19, NET). He also says the law was a guard to keep us safe and a “guardian” or “tutor to bring us to Christ, that we might be justified by faith” (Gal. 3:24, WEB). The law defines sin for us and reveals the penalties for breaking God’s covenant law. As transgressors of the covenant, we deserved to inherit the curses contained in the covenanting words (Deut. 11:26-32; 27:1-28:68).

The only one who perfectly kept God’s covenant was Jesus Christ, and so He’s the only one who truly deserved to inherit all the promises. Once Christ inherited, He died and “willed” those promises to us. Now, “if you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s descendants, heirs according to the promise” (Gal. 3:29, NET). Moving from the Old to the New Covenant is like going from being slaves to being “sons with full rights” (Gal. 3:23-4:7).

No Going Back To the Old

Now we get to the passages of Galatians that I struggle with, because I understand that the Old Covenant is over and we’re under the New Covenant, but I also know from Jesus Himself and from other apostolic writings that God’s law still exists. The confusing part is that most of God’s law that we have recorded in scripture was given as part of the Old Covenant. So I struggle sometimes with figuring out what in the Torah is God’s timeless, enduring Law and what is part of the Old Covenant that ended with Jesus’s sacrifice.

Formerly when you did not know God, you were enslaved to beings that by nature are not gods at all. But now that you have come to know God (or rather to be known by God), how can you turn back again to the weak and worthless basic forces? Do you want to be enslaved to them all over again? You are observing religious days and months and seasons and years. I fear for you that my work for you may have been in vain. I beg you, brothers and sisters, become like me, because I have become like you. You have done me no wrong!

Galatians 4:8-12, NET

Remember that he’s talking with Gentile converts, so the “beings that by nature are not gods at all” are most likely references to false gods worshiped by people in the Galatian region. But Paul is also talking about not being enslaved to the Old Covenant, so we read this part about “observing religious days and months and seasons and years” and readers wonder if Paul means something pagan, something added by the Jews, or the sabbaths outlined in Leviticus 23. Many commentators say it’s the Sabbaths, but Jesus kept the Sabbath and the author of Hebrews (very likely Paul) concludes, “a Sabbath rest remains for the people of God” (Heb. 4:9). Additionally, Paul clearly instructed the Corinthians to keep the Feast of Unleavened Bread (1 Cor. 5:8). Whatever he’s talking about here in Galatians, it isn’t getting rid of God’s holy days.

Contextually, since Paul was talking about the time before they knew God at all, it seems most likely that he’s referring to something other than the Biblical holy days. It may be that the Galatians practiced some kind of religious syncretism and continued keeping their pagan festivals. Or perhaps he’s rebuking the Galatians for keeping the holy days wrongly (perhaps transactionally, as if by keeping these days God will “owe” them something), as ancient Israel did when God told them, “I cannot tolerate sin-stained celebrations!” (Is. 1:13, NET).

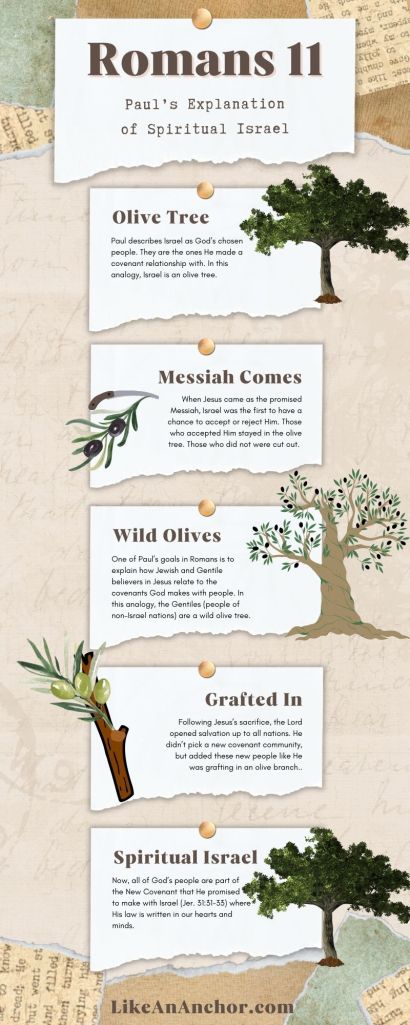

Paul then made a personal appeal to the Galatians to hear him and come back to the truth. He accuses those who’ve been preaching a distorted gospel of trying to isolate the Galatians for their own gain (Gal. 4:13-20). Then, he returns to the topic of being under the law and this time uses Abraham’s children as an allegory. It roughly parallels Romans 11, in that Paul is contrasting the Jews who didn’t follow the Messiah with the Jews and Gentiles who accept Jesus and inherit the promises of God (Gal. 4:21-31; Rom. 11).

A Christian’s Freedom

As Paul begins to wrap up this letter (ch. 5-6), he moves to talking about the freedom of New Covenant believers to put God’s way of life into practice by living in faith and love. Essentially, the second half of Galatians is an expanded version of a statement he makes in his first letter to Corinth: “Circumcision is nothing and uncircumcision is nothing. Instead, keeping God’s commandments is what counts” (1 Cor. 7:19, NET).

You who are trying to be declared righteous by the law have been alienated from Christ; you have fallen away from grace! For through the Spirit, by faith, we wait expectantly for the hope of righteousness. For in Christ Jesus neither circumcision nor uncircumcision carries any weight—the only thing that matters is faith working through love. You were running well; who prevented you from obeying the truth? This persuasion does not come from the one who calls you! …

For you were called to freedom, brothers and sisters; only do not use your freedom as an opportunity to indulge your flesh, but through love serve one another. For the whole law can be summed up in a single commandment, namely, “You must love your neighbor as yourself.”

Galatians 5:4-8, 13-14 NET

As we’ve been talking about for a good part of this past year, faith involves active, relational loyalty. It’s part of keeping covenant with God that we appreciate His gift of grace by honoring Him, patterning our lives after Him, and obeying His commands. At the same time, we must never think that the actions we take in response to God saving us are a way for us to save ourselves. Jesus is the one who saved us. He even frees us from being under the law in the sense “that law is not intended for a righteous person, but for lawless and rebellious people, for the ungodly and sinners, for the unholy and profane” (1 Tim. 1:9, NET). If we aren’t any of those things (i.e. we’ve repented of sin, believe in Jesus who cleanses us from sin, and follow Him faithfully, repenting if we miss the mark), then we aren’t under any penalty from breaking the law.

But I say, live by the Spirit and you will not carry out the desires of the flesh. For the flesh has desires that are opposed to the Spirit, and the Spirit has desires that are opposed to the flesh, for these are in opposition to each other, so that you cannot do what you want. But if you are led by the Spirit, you are not under the law. Now the works of the flesh are obvious: sexual immorality, impurity, depravity, idolatry, sorcery, hostilities, strife, jealousy, outbursts of anger, selfish rivalries, dissensions, factions, envying, murder, drunkenness, carousing, and similar things. I am warning you, as I had warned you before: Those who practice such things will not inherit the kingdom of God!

But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control. Against such things there is no law. Now those who belong to Christ have crucified the flesh with its passions and desires. If we live by the Spirit, let us also behave in accordance with the Spirit.

Brothers and sisters, if a person is discovered in some sin, you who are spiritual restore such a person in a spirit of gentleness. Pay close attention to yourselves, so that you are not tempted too. Carry one another’s burdens, and in this way you will fulfill the law of Christ. For if anyone thinks he is something when he is nothing, he deceives himself. Let each one examine his own work. Then he can take pride in himself and not compare himself with someone else

Galatians 5:16-6:4, NET

That’s a long quote, but I think it’s key to understanding Paul’s take-away points from this letter. His insistence that the Galatian believers don’t need to be circumcised or keep the law does not exempt them from following God’s commandments. In fact, he issues the strict warning that those who sin will not inherit God’s kingdom! Living in the Spirit and walking by faith (as is expected of New Covenant Christians) means behaving in accordance with the spirit and therefore fulfilling the law of Christ (see also 1 Cor. 9.21). It’s a higher, better level of commandment keeping than the Galatians were trying to do by focusing only on the physical sign of an old covenant and not on the heart-level transformation that God looks for in His people.

Paul wraps up this letter with an admonition to teach truth, encouragement to keep doing good, and another reminder that the people who’d deceived the Galatians just wanted to avoid persecution and make themselves look righteous (Gal. 6:6-18). In conclusion, Galatians was written to address a specific problem in a specific church region at a specific time. But it still has a lot to teach us today when we take the time to put Paul’s words in context and understand his argument. Like the Galatians, we must be wary of letting ourselves get entangled in ideas or practices that sound righteous, but really distract us from faithfully following Christ and fulfilling the law of God by truly practicing love for Him and our neighbors.

Featured image by Marissa Martin

Song Recommendation: To God Be The Glory ( Royal Albert Hall, London)